Rogers Files Part II: An intriguing second act

By BRANDON HURLEY

Sports Editor

sports@beeherald.com

EDITOR’S NOTE: The following story is the second part of a two-part series on Jefferson High graduate Joe Rogers, an athlete who won the school’s first three state titles and later went on to enjoy a fruitful career. Part I, from the March 20 issue of the Jefferson Herald, can be found here: https://bit.ly/3bDWxAt

----

Despite his electrifying speed and historical dominance, Joe Rogers made his most significant impact in the game of football.

The 1930 Jefferson High graduate initially burst on to the athletic scene with the Jefferson Ramblers record-setting football team.

And man, were they ever spectacular. The Ramblers were the 1920s version of the “Steel Curtain,” Pittsburgh’s vaunted defense from the 70s. Jefferson ascended the ranks, becoming one of the most staunch and relentless defensive units in state history.

Rogers shined as the starting tailback during a remarkable run throughout the 1928 and 1929 seasons, the former of which included a perfect season and a piece of an unofficial state championship.

The Ramblers strung together a state record 15-game shutout streak which spanned both 1928 and 1929 (The streak still stands today as No. 1, though its’ not acknowledged in the IHSAA record books).

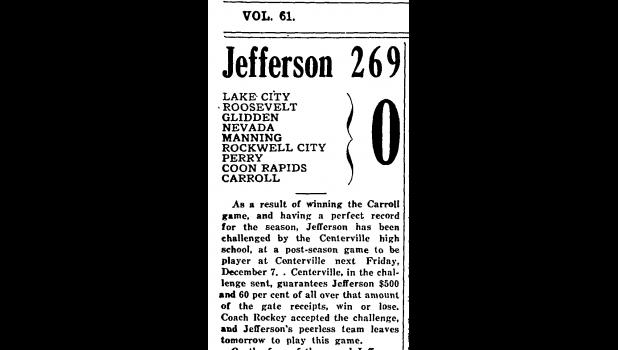

The Ramblers possessed Iowa’s best defense throughout the 1928 campaign, which was nearly undisputed, tallying a perfect 9-0 regular season record without allowing a single point, out-scoring their opponents by an insurmountable difference of 269-0.

Jefferson romped its way through the final regular season game held Thanksgiving Day, Nov. 29 against local rival Carroll. The Ramblers absolutely demolished the hometown Tigers, securing a perfect season with a dominant 19-0 victory. Some of their other notable victories along the way included a 52-0 shellacking of Lake City and back-to-back 50-point triumphs, a 56-0 win over Nevada followed by a 51-0 dismantling of Manning.

The unblemished regular season set the table for an unusual postseason contest. Centerville, with it’s spotless 8-0-1 record, felt they were the best team in the state, and in an era with no playoff system (the state would finally enact a postseason tournament in 1972), Centerville issued a challenge.

The school invited Jefferson to travel to Centerville for a December matchup, creating the de-facto state title game.

Though the deck was stacked against Rogers and company, the Ramblers put up quite the fight. After they navigated the nearly three hour drive to the Missouri border (it was the longest road trip in Jefferson history up to that point, more than 300 miles round trip), the 1928 gridiron stars were greeted with horrendous field conditions. The ground had frozen a few days earlier then thawed in the ensuing week, creating a sloppy, muddy mess. If that weren’t enough, the Centerville players were gigantic in comparison to Jefferson, outweighing each of the visitors by a good 15 pounds. The home crowd fed off this notion, taunting the Jefferson athletes, chanting derogatory phrases, including the most hurtful of sorts “Take the babies home to their mommas.”

The Ramblers were focused, and despite a field that greatly hindered their great rushing attack, held its own thanks to the historic defense.

Former Des Moines Register sportswriter Sec Taylor attended the state’s premier football game, and told the story of a contest pitting strength against strength. Two bull-headed lines, trying to force one another into a mistake. No one could gain an inch, as one giant defensive stop after another kept the contest at a stalemate.

“The game resolved into a battle of lines, both of which were well coached and held up remarkably well,” Taylor wrote. “Centerville had a decided advantage in weight, but there the advantage ended, for the smaller Jefferson backs (led by Joe Rogers) battled nobly. The tackling of both teams was superb.”

The soggy and frigid conditions struck in the third quarter as Jefferson was driving for the go-ahead score. Rogers found himself smack dab in the middle of the biggest play of the “championship game.” Jefferson quarterback Dean Lindsey was orchestrating a drive that would likely go down in school lore, and shifted his focus toward the tailback.

“The excitement started in the third period. With (Dean) Lindsey, a passer, who shoots the ball as if it comes from a catapult, and with accuracy, too, tossing the ball, two beautiful passes were completed,” Taylor wrote as Jefferson maneuvered its way for the potential game-winning score.

Lindsey scrambled around on third down and found Rogers open in the end zone. As the ball hurtled toward him, the track star slipped while lunging for the still airborne pigskin, only able to extend his finger tips toward it, as it careened downward onto the cold, wet ground for an incomplete pass and a loss of downs.

Lindsey redeemed himself on the ensuing drive, making the play of the game.

The two-way player tallied a game-saving tackle during Centerville’s next possession, as he chased down their running back who had burst around the outside for 45 yards before Lindsey brought him down on the 11 with a “Beautiful flying tackle.” The back had evaded the entire Jefferson team and looked to have obtained a game-winning score before Lindsey arrived.

In the end, redzone defense was instrumental, as neither team really threatened to score outside of Rogers’ drop.

The Ramblers remained stout and strong throughout, riding the prowess of their defense, silencing the arrogant Centerville athletes. The triumphant 0-0 tie felt like a victory, as it secured Jefferson a piece of the unofficial state championship, the only such honor in Jefferson’s football history, finishing the year with a 9-0-1 record.

The high school squad commemorated the season in an odd way at their annual banquet. The team congregated at the home of Mr. and Mrs. G.C. Richardson and relegated to the backyard. A mock funeral broke out, as the Ramblers physically “buried” each of their nine opponents that fall, digging small graves for dolls representing the schools. They took it even a bit further, recalling a rainy and muddy victory over Rockwell City near the tail end of the schedule. As it was written in the Jefferson Bee, the athletes buried a “colored doll,” representing how the athletes on the field looked, as the mud caked onto the uniforms, causing the spectators to “possibly mistake them for a team of Negros.”

Despite that blatant racism, Rogers escaped to carve out a successful college football career at William Penn University in Oskaloosa. He was an instant success, joining the basketball and track and field units as well, becoming one of the most popular athletes on campus.

Rogers was named captain of the 1934 William Penn football squad, making enough of an impact in football and basketball as well as track – he set a school record in the 100-yard dash – to warrant an induction into the school’s athletic hall of fame in 1991.

Once Rogers tossed his athletic gear to the side and began his coaching career, a chance encounter a few years in sparked a remarkable opportunity.

–– • ––

Harold “Fritz” Crisler and the University of Michigan were well on their way to building their own perfect season when the legendary coach made a life-changing recommendation.

Crisler’s name adorns the Michigan men’s and women’s basketball arena, which was built in 1967. The Hall of Fame coach was quite the innovative mind, introducing the winged, maize and blue Michigan helmets back in

1938. Crisler was hoping to easier differentiate the Wolverine wide receivers from the defenders, which is why he came up with the unique helmet design, which he also deployed when he was head coach at Princeton. When Crisler arrived on the Michigan campus in Ann Arbor, the Big Ten school was enjoying a spectacular athletics revolution. Their athletic department was the cream of the crop, which Crisler later manned through the 1968 academic year.

Crisler was known for his military-like precision. He was a tall, well-built specimen who was rarely known to smile. His players reflected Crisler’s businesslike attitude on the field, hardly making mistakes.

Crisler was also a key member of the college football rules committee, building off his installation of the now common platoon system.

When Crisler’s Michigan team was impacted by World War II, he was left with a surplus of freshman and only a few, key veterans. Instead of trotting out the same freshman athletes on both sides of the ball, he decided to create defensive and offensive specialists.

The new scheme helped power Michigan to one of the most successful seasons in school history, as the Wolverines tallied a perfect 10-0 season in 1947, capped by a 49-0 shutout of USC in the 1948 Rose Bowl. The thrilling run earned Michigan the honors of National Champion while Crisler was named college football’s coach of the year. It was the pinnacle of the legend’s career.

During that magical season in which the Wolverines were dubbed the “Mad Magicians,” Crisler still found time to adhere to a close friend of his, offering an opportunity of a lifetime.

—* —

On paper, the Rogers-Crisler relationship is a tad puzzling. How does Michigan’s hall of fame football coach and a nondescript high school teacher in Mason City, Iowa strike up a strong, professional relationship? Two drastically different locations with equally as differing talent pools. Eventually, the pair grew close and blossomed into a partnership that often spawned ideas and thoughts over the years.

After various coaching and athletic director stints at Maxwell, Manning and Rockwell City, Rogers really came into his own at Mason City. He ran into the great Fitz Crisler at an IHSAA coaching school held in Clear Lake after spending a few seasons building the Mason City program.

The year was 1946 and the two hit it off instantly.

Rogers and Crisler connected over the intricacies of football. Their friendship wasn’t as unlikely as one would imagine if you consider the circumstances. The fact the father of “two-platoon football” recommended Rogers for a job in Michigan was a massive vote of confidence.

The Jefferson graduate and football coach took many of his cues from Crisler. He modeled his system after the legendary coach. Rogers deployed a single wing attack, which Crisler also implemented, but the former Rambler also sprinkled in a bit of the “I” formation, conducive to his love for the run game.

Rogers was a patient coach, well-mannered but with a strong dose of confidence. He was also a socialite, and was known for his ability to mingle with various administrators and whoever wanted to chat football with him. Rogers was a true student of the game, attending several different coaching clinics throughout his career, a life-long learner, if you will, which is what initially drew Crisler to the high school coach. An article in the 1952 News-Palladium in Benton Harbor, Michigan hinted at Rogers serving a role as a volunteer assistant on a few occasions. Crisler was thrilled by Rogers dedication to the sport of football.

“He was so impressed with him that he had Rogers do a bit of scouting for him and sit on the bench with him at several games,” the article read.

Rogers acquired a 67-30 record in 12 years while coaching all over Iowa. While he never won any state championships, he only once possessed a losing season. Rogers also was an assistant for various basketball and track and field teams.

After a couple of years sharing lunches and notes with each other (sometimes beneath the shade of a tree, as pictured in a Mason City Globe Gazette article), Crisler gained such an appreciation for the small-town Iowa man he decided to throw his name into the Michigan high school coaching circles.

Per Crisler’s recommendation, Rogers was offered a position at Benton Harbor High School in Benton Harbor, Michigan as their head football coach and as the school’s athletic director. Though at the time Benton Harbor held a population of 20,000 residents, the school district drew students from all over the region, boosting its student body population to 1,300 kids. This was a major step up from Mason City and Iowa prep football - Rogers jumped at the opportunity.

The News-Palladium latched on to Crisler’s unusual admiration for Rogers, penning the headline at the time of his hire in 1947 “(Rogers) recommended highly by ‘Fritz’ Crisler.”

The paper, likely encouraged by Crisler himself, respected Rogers’ achievements in Iowa.

“He is a thorough taskmaster and made it pay off with a fine record in the toughest conference in Iowa prep circles,” read the News-Palladium article.

Rogers engineered the Benton Harbor football team for nine years, compiling a overall record of 45-24-10. Though Rogers retired from coaching in the mid-50s, he stayed with the Michigan school district for another 16 years in their athletic department. Like Crisler, perhaps taking a cue from his historic career, Rogers became a pioneer of sorts within the game of football, holding a position as executive secretary for the Michigan High School Athletic Directors Association while he also was Michigan’s advisory member for the National High School Football rules committee. In turn, Crisler was a big proponent of improving the game of football as well, often spending his later years dabbling in the world created by the College Football rules committed. The duo, though on two different levels of football, always strived to push the game forward, with rules tweaks and safety concerns, improving the flow as much as possible. Rogers and Crisler likely spent hours and hours together discussing the game of football, as the University of Michigan and Benton Harbor are separated by just two hours of driving time.

—* —

Rogers’ torch-bearing earned him respect throughout the state of Michigan, earning him an induction into both the Benton Harbor High School Hall of Fame as well as the Michigan High School Coaches Hall of Fame. During Rogers’ Michigan Coaches induction in 1965, he was given a Whirlpool dishwasher. Rogers was also inducted into the William Penn athletics hall of fame in 1991, pushing his Hall of Fame representations to three. A Greene County High School hall induction surely isn’t too far off as well.

Adding to generous personality, Rogers was a staunch family man, as he and his high school sweetheart, Jean Alice Grauer, were married for 70 years, eloping during Joe’s college days. Together, the couple raised three kids; Joe Allen, John and Janet.

Joe Rogers lived a long and fruitful life, striving to serve others and share his many passions. He helped found the Wolverine Benefit Association and spent 21 years within the organization, serving as a board member and vice president.

Rogers eventually passed away on Jan. 15, 2001 at the ripe age of 90 in Kalamazoo, Michigan. At his passing, Joe and Jean were grandparents to 11 grandchildren and 23 great-grandchildren. Hopefully, those Rogers descendants carry on the great tradition of the legendary, Joe Rogers, a Jefferson icon.

- Log in to post comments