THE EARLY LEAD: A HERO AND A COACH

By BRANDON HURLEY

Sports Editor

sports@beeherald.com

The explosive and deadly battlefields of Germany are drastically different from the physical gridiron of LA, but, the late Don Clark combined the two quite beautifully, because, frankly, he was a natural-born fighter. Maybe it was how the two compared - success in a war or on the football field relies heavily on preparation and perseverance, characteristics Clark greatly possessed.

The Churdan native was well-liked and respected, whether he was firing a rifle or calling out plays. It’s a funny and exhilarating thing what a few hours of research can conjure up when you aren’t exactly looking for this particular topic. I stumbled upon Clark and his coaching accolades by chance, and as the rabbit hole of his curious career wound its way deeper and deeper into the crevices of the internet, it became even more tantalizing. Don Clark’s USC career caught me by surprise and it inspired me. It taught me to look in places we likely wouldn’t go near, to battle and take risks. To focus on your family, even when your career seemingly is hitting its stride. It’s a great piece for today’s world. Priorities are important.

But what really struck me hardest was how unusual it was that a major Division I coach was born on a tiny Churdan farm. Not only that, but he also became a war hero in the midst of his football days. There’s no way I wasn’t going to share this story. That’s what Clark continually provoked - ambition and strength. He fought for what he believed in and defended at all costs.

From the subtleties of a northeastern Greene County farm to the bright lights of LA, the late Clark possessed an unusual knack for pioneering.

The one-time San Francisco 49er piloted USC during one of its most tumultuous eras and even helped kick-start the career of an NFL front office legend. Clark compiled one of the most interesting resumes to come out of Churdan, and today, we share his tale.

He played guard for the Trojans in the 1940s, left school to fight in World War II, only to return to California and complete his athletic eligibility.

But it began a few miles northwest of Churdan on a small family farm owned by his father, John Clark. Donald attended a country school north of Jefferson, eventually earning the nickname ‘Barney’ before later enrolling at the Dana High School. Clark had three brothers; John Jr., Tripp and Frank while he also had a sister, Kathryn Foster, who later married Paul Foster, moving back to Scranton with him before passing away in 2008. Clark also had two other sisters. The large Clark family uprooted and moved to Los Angeles when Don was 15, leaving the cozy confines of rural Iowa for the bustling economy of Hollywood.

Clark excelled during his high school days in California, securing the student council presidency his senior year, parlaying that into a football scholarship from the nearby University of Southern California. He played guard for the Trojans for two years, securing a varsity letter in 1942 before his collegiate playing career was interrupted by the climax of World War II.

Clark played a pivotal role overseas for roughly three years, serving in the 99th division as a rifleman, fighting in the Battle of the Bulge. Great Britain’s Winston Churchill called it the “greatest American battle of the War.” The six-week contest took place in the region of Belgium, which was under Adolf Hitler’s control, from December 16, 1944 to Jan. 25, 1945. The “Battle of the Bulge” was the deadliest and most brutal fight in American history, taking the lives of more than 100,000 German soldiers. The Americans and Clark not only had to contend with Hitler and his fierce Army, but they also fought through intense cold, dense fog and snow as well as freezing rain, inflicting a string of natural injuries including frostbite and pneumonia.

Clark was part of a rifle platoon for seven months in Hofen, Germany, surviving a lengthy stretch of dangerous conditions, enduring gunfire and remote attacks.

As told in “Battle Babies: The Story of the 99th Infantry Division in WW II,” the exact mission and location of Clark’s division were kept tightly under wraps for many, many years. They often patrolled enemy lines, investigating the dangerous territory. They were later instructed to attack the Germans, eventually freeing several hundred Belgian Prisoners of War.

The U.S. Department of Defense reported that more than half a million Americans tangled in the now legendary battle, roughly 42,000 American soldiers either died or went missing with more than 47,000 injured. (Courtesy of the U.S. Army).

“The worst of it was in Hofen,” Clark was quoted saying in an interview referenced in his LA Times obituary in 1989. “That’s where my battalion was during the first part of the Battle of the Bulge. We were surrounded in that little town for 10 days and under constant shelling and mechanized attacks.”

He essentially escaped WWII’s bloodiest battle with a minor injury, in relative terms, when a German anti-aircraft missile exploded nearby, shattering six of his teeth.

Miraculously, Clark was unfazed by the tremendous heartbreak and utter chaos of WWII and returned to USC to complete his college education and fulfill his commitment to the Trojan football team.

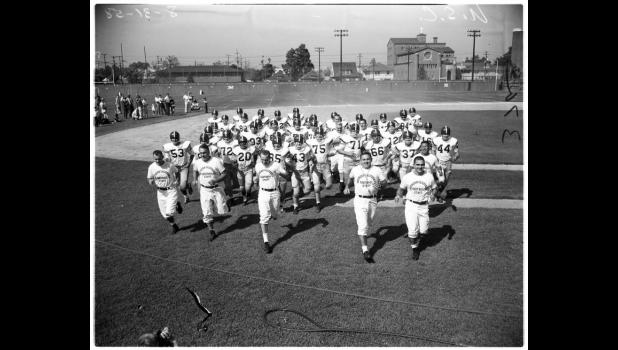

Clark confidently arrived on the USC campus with two years of eligibility left in 1946, making a fairly seamless transition, He was eventually named team captain in 1947, his senior year, which he helped lead USC to the Rose Bowl against Michigan.

Clark’s play was strong enough to gain notice in the professional ranks, as he suited up with the San Francisco 49ers for two years, before retiring to immediately settle into a job as defensive coordinator at Navy in 1950. He held down his post with the Midshipmen for just a single year before USC head coach Jess Hill asked him to return to LA. Clark served his role as an assistant for six years under Hill, establishing a strong bond with the coaching staff and the players.

Clark rapidly honed his coaching chops and his peers took notice. He engineered a stout and physical defense that powered USC to a Rose Bowl victory in 1952, tallying a 10-1 record and rising as high as No. 2 in the AP rankings. The Trojans were a dazzling 23-7 the first three years Clark spent as a defensive assistant

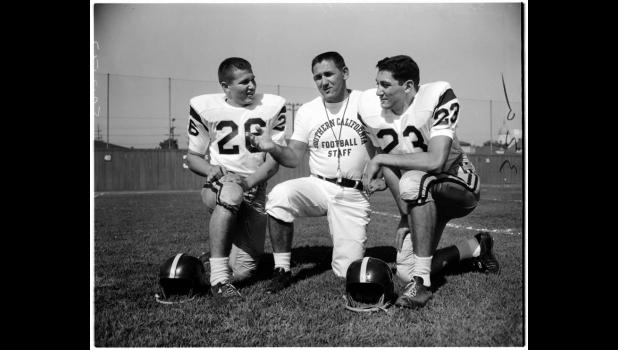

That success, despite his intimidating exterior, detailed by the San Bernardino County Sun as “powerful-looking with a bristling crew-cut and his wrestler’s face, set squarely on a brief neck and massive shoulders” drew the interest of his players, alumni and the pep club thanks to his “sensitivity” and his admiration for his job and family. He didn’t drink nor smoke, and was loyal. The large group of supporters petitioned Clark to become the new USC head coach when Hill took a job as USC’s athletic director following the 1956 season. Clark was a hot commodity that offseason, choosing the Trojans over other coaching offers from the 49ers, the LA Rams and a Canadian football team. Clark was just 33 when he accepted his first head coaching position, and it was, at the time, perhaps not the most promising of job prospects.

Clark was in for a real uphill battle despite USC’s usual ranking among the nation’s elite. Though he spent just three years as USC’s head coach, Clark bravely swallowed the punishment from a prior recruiting scandal, the backlash of a case of brutal physicality and the dissolution of USC’s athletic league, the Pacific Coast Conference.

The Trojans won just a single game in Clark’s head coaching debut in 1957, leading USC to a 1-9 record. He was tasked with a monumental climb that inaugural year. The Trojans were without the “errant eight,” which media outlets named the eight men suspended from the USC team for accepting illegal benefits. (See, even 60 some years ago recruiting was rather shady). The NCAA found USC guilty of paying recruits in 1956, which resulted in a two-year bowl ban and a hefty fine while they were also placed on probation for two years. Because of these sanctions, Clark was dealt a raw hand. Eight of his most veteran players were no longer available and he was cursed with just 15 returning lettermen from the previous season, which showed in their single-win campaign. The injuries piled up as well, putting an unfair exclamation point on Clark’s debut.

The team improved during Clark’s final two years at the helm, going 4-5-1 the following season before tallying it’s first winning season in four years with 8-2 record in 1959. Supporters weren’t completely confident in Clark prior to the eight-win season, as he’d won just five total games in two years. But he easily put the doubters to bed with the Trojans success. USC finished ranked 14th in the 1959 AP rankings. The Trojans began the fall slate as one of the nation’s best teams, winning eight straight, including wins over 14th-rated Ohio State and 18th-ranked Washington before losing their final two contests to heated rivals UCLA and Notre Dame. The Trojans were quite the turnaround success story, doubling their win total from 1958, eventually reaching as high as No. 3 in the nation during the winning streak. The Trojans two losses came by a total of 17 points, a 10-3 defeat at the hands of UCLA and a 16-6 stunner to Notre Dame.

The late Al Davis, former owner of the Oakland Raiders, was Clark’s most notable assistant during those days. In his Hall of Fame induction speech in 1992 - which commemorated Davis’ years as a NFL coach, commissioner and long-time owner - he mentioned how “the late Don Clark, a magnificent human being, hired me as an assistant coach.” Al Davis came over to USC from the Citadel, and quickly made himself known in the professional ranks after leaving the LA campus a year later.

Clark shocked the college ranks by immediately resigning following the 1959 season even though he had just completed his best - and only winning - campaign to date. He announced his decision in mid-December and was optimistic during the ensuing press conference.

“I never intended to make coaching my life career,” he’s quoted saying in a UPI press release. “I find myself unable to let pass the opportunity now being afforded me.”

He later added that he was proudly thrilled with how well the program recovered and developed during his brief stint.

“My staff and our players have successfully answered the challenge presented when I was promoted,” he said in the press conference.

John McKay was named Clark’s successor, and was also shocked by his decision to hang it up so soon, but obviously overjoyed with the new promotion.

“(I am) naturally surprised and thrilled with the opportunity,” McKay was quoted saying. “This happened so suddenly that I believe everyone is stunned by coach Clark’s decision. The coaching profession will miss a man of his caliber.”

Many newspapers and media outlets around the country assumed he was hanging it up due to continued backlash from one of his players assaulting an opponent, but Clark said he wanted to spend more time with his seven children and his wife, Dorothy, departing a year before his contract was up.

The controversy rumored to have forced Clark out was not by his own doing. Mike McKeever, a USC defensive lineman, brutally tackled California running back Steve Bates in late October of that year. Video had shown Bates clearly out of bounds when McKeever elbowed him in the face, fracturing his cheekbone, breaking his nose and dislodging several teeth. The injury sent Bates to the hospital and prevented him from taking the field again that season. Cal coach Pete Elliot was furious that McKeever was never severely punished, and openly criticized coach Clark. The Churdan native vehemently defended his athlete, saying it was not an intentional elbow, and he didn’t plan to further defend his squad’s aggressiveness.

“I personally don’t feel that I must apologize for the actions of the USC team at Berkley,” Clark said in an AP report. He later said the constant heat on the program greatly hindered their preparations the final two weeks of the season, which could have very well been a cause for the pair of upsets.

The University of California, as a whole, would not back down quietly. The student body urged the Bears to never take the field again against USC as long as McKeever was still a member of the team. It was quite the hot button issue throughout the final stretch of the1959 season, dominating headlines for several weeks. USC president Norman Topping publicly apologized to Cal, which did not sit well with the football program. It undermined Clark’s authority and left the players wondering if they were playing the game the right way.

Following his coaching career, Clark built quite the life for himself, fathering another child with his wife, Dorothy to bump the family tally up to eight kids. He took a roll as vice president of his family’s business, Prudential Overall Supply Co, a clothing company that was run by his brother, John. He later ascended to the seat of president before his death.

Sadly, Don Clark died in April of 1989 at the age of 65 of an apparent heart attack while jogging in Huntington Beach, California, a few miles southeast of Los Angeles, thus closing the book on a captivating career, one that deserves its shine among the confines of Greene County.

- Log in to post comments