A surplus of gratitude

By ANDREW MCGINN

One can only imagine the sheer number of Nazis that were killed, in Jefferson alone, in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The boys of Steve Haupert’s generation fought them in yards, in parks, in wooded areas behind their houses and even in family rooms until every last “Kraut” was mowed down or else Mom put an end to the Battle of the Bulge.

Virtually every one of their fathers had served in World War II, and their fertile imaginations were stoked by the discovery of bits and pieces of military gear at home — a stray helmet here, a forgotten machete there, a random knife, a box full of medals.

It hardly mattered that their dads were mum about their experiences. Boys had TV shows like “Combat!” and 10-cent comic books like “Our Army at War,” featuring the exploits of Sgt. Rock, to fill in the key details.

“Everybody had a little bit of military equipment,” Haupert, now 70, recalled.

Sixty years later, his personal collection of military equipment from World War II would easily make him the most popular kid in the neighborhood.

The boy who was fascinated by World War II became a man who could legally buy a vintage, .30-caliber M1 Garand in firing condition.

The kid who once wielded a plastic submachine gun made by Mattel in the timber at the bottom of Jackson Hill is now the adult who can casually walk around his house and say things like, “That’s an inert mortar round.”

“It’s been a lifelong passion,” said Haupert, a former Greene County sheriff and a 1967 graduate of Jefferson High School.

There are fewer and fewer of the nation’s 16 million World War II veterans every day, and many are taking their stories with them.

“It’s important we remember,” he said.

In hindsight, Haupert wishes he would have sat down with his uncle Jack before he died in 1996 — but short of that, he cherishes the knives and ammo boxes that Jack Haupert brought back from Tinian, the island in the South Pacific famous for launching the Enola Gay with an atomic bomb in her belly at 2:45 a.m. on Aug. 6, 1945.

More than ever, Haupert wants to display his collection somewhere publicly for the first time, mostly because he can (he’s now retired) but partially because he thinks he should.

“It’s like the Holocaust,” he explained. “We now have people who think that didn’t happen.”

Sure, Haupert has his share of rifles and bayonets, but in exploring his collection, what truly amazes is the realization that our fathers, uncles and grandfathers not only had to save the free world — but that they had to lug around so much stuff while doing so.

The average Marine in World War II carried between 65 and 70 pounds of basic weapons and equipment.

The M1 Garand itself weighed nearly 10 pounds.

No object is seemingly too mundane for Haupert’s collection.

At the heart of it is web gear, the various items soldiers and Marines would have worn around their waists and on their backs.

“I’ve studied picture after picture,” Haupert said, “and they all vary. Some had a shovel. Some had a machete.”

Going from pouch to pouch turns up everything from a compass to bandages, all manufactured for use during the war and all in such pristine condition that you half-wonder where Haupert keeps his time machine.

A vial of halazone tablets looks as new as the day Abbott Laboratories bottled it in “North Chicago, Ill, USA.” A soldier would have dropped one of the tablets into his canteen and shaken it up in order to purify the water for drinking.

In another pouch, an olive-drab tube reads, “Lipstick, antichap.”

“To have correct gear is as important to me as the rifle,” he said.

On this day, Haupert had everything laid out on the floor of his living room in a way that made it look like Easy Company was camped out for the night.

You could practically smell the unfiltered Chesterfields.

One complete set of gear pulled together what a Marine would have sported early in the war, including an ammo belt, grenade carrier and even the canvas gaiters that covered the calves and were notoriously uncomfortable when wet. Of note, Haupert explained, are the dog-eared canteen covers — the double flaps that cross were unique to the Marines in the war.

“I buy every book that has a lot of pictures,” he said. “I sit with a magnifying glass and look at the pictures.”

A nearby M1 Garand was manufactured in February of 1943, and still has its original barrel — a rarity considering that M1 ammo initially had a corrosive powder in it that caused many barrels to be replaced.

The M1 automatically ejected an empty clip once its last round was fired, that famous “ping” in every World War II movie.

Haupert has been collecting for 40 years, but has been married for what will be 43 years in June.

“She’s always known,” Haupert said of his wife, Carla. “She doesn’t know how much.”

By her own admission, “It’s not a real high interest of mine,” Carla Haupert said. “I just kind of tolerate it.”

Haupert doesn’t own any automatic weapons — that requires a special permit — but he does have several of the long magazines belonging to the M3A1, the no-frills submachine gun known as a grease gun.

Many of Haupert’s items were acquired in the days when military surplus was still plentiful.

“A lot of the good, U.S.-made stuff from the ’40s and ’50s is gone,” he said.

His collection started simply enough with the gear his dad, Jay, brought home from the Army.

A 1939 graduate of Jefferson High School, the now-late Rex “Jay” Haupert had been afflicted with polio at age 4 — causing his right foot to turn out and leading him to walk with a limp — but he nevertheless did his part, serving in a communications unit in Brazil.

Steve Haupert recalls being 7 or 8 when he first discovered his dad’s stash of equipment, much of it stenciled with “U.S.” in black.

Growing up on West South Street, every boy at that time on the block was allowed to play with their dads’ mementos, except that Jay Haupert would only allow Steve to wear the liner of his steel helmet.

“I remember Steve Nelson had a dangerous machete,” Haupert said.

Nelson’s dad, Magnus, was principal at the local elementary school. And a machete wasn’t all he had from his 16 months in Europe during the war.

Magnus Nelson reportedly also possessed a little piece of Hitler’s throne — that is, his toilet.

“We’d look at that,” Haupert said, “and just marvel.”

Souvenir hunting was so prominent during the war that it later factored into the TV miniseries “Band of Brothers.” In it, one soldier goes from D-Day to the Battle of the Bulge obsessed with finding a German Luger.

When Magnus Nelson later died, Haupert bought the aforementioned machete at his estate sale, in addition to a German bayonet that he ferried home.

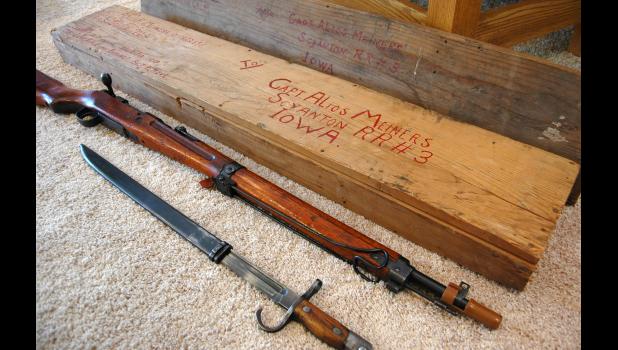

With a satisfying click, Haupert can now snap Magnus Nelson’s German bayonet onto the end of a German rifle, a Mauser 98k, brought home by another local veteran, Tom Black, who passed away in 2010.

Numerous items in Haupert’s collection were acquired from local veterans he knew or else their estates.

Bernard Dittert, who had been in D-Day, once gave Haupert a prized Boker fighting knife. In 2002, Haupert served as a casket bearer at his funeral.

Haupert came to own an Imperial Japanese rifle once belonging to Al Meiners in a roundabout way. A sheriff’s deputy whose dad had been the auctioneer at Meiners’ estate sale had it but was looking to sell.

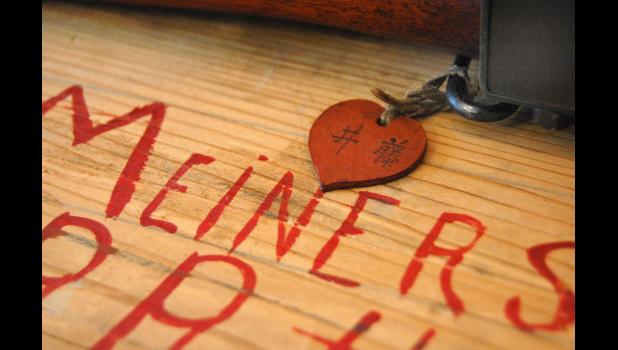

The rifle — an Arisaka Type 99 — even came in the original wooden crate that was used to ship the rifle and a Japanese bayonet home to “Capt. Alios Meiners” on Rural Route 3 in Scranton.

Accompanying paperwork shows that Meiners (whose first name was actually spelled Alois) received permission on Jan. 17, 1946, to own or mail the rifle.

As commanding officer of B Troop of the 5th Cavalry Regiment — part of the famed 1st Cavalry Division — Meiners appears to have been in command of an entire town, Fujisawa, during the U.S. occupation of Japan, as other papers suggest.

Meiners had been a veteran of Luzon in the Philippines before accompanying the rest of the 1st Cav to Japan following the Empire’s surrender in August 1945.

Included in Haupert’s purchase of the rifle was a fascinating group of letters written to Meiners from Japanese citizens.

They reveal a nation on its knees.

In one letter dated Jan. 2 (1946), the wife of an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy — Vice Admiral Ryuichiro Enomoto — actually asks Meiners if they can have his kitchen scraps.

“We lost our home in Tokyo in one of your raids in April,” she wrote in English, “and are trying to start anew here and your garbage helps on our tiny farm.”

Haupert knew Meiners as an auto mechanic whose shop was located on Lincoln Way in Jefferson. (His old shop is the brick building across the street from the former Deep Rock station.)

But the notion that Al Meiners was once something far more than that — just as Magnus Nelson was once something more than an elementary school principal — is the very story of World War II, the largest armed conflict in human history.

If only Haupert’s collection could talk.

INSIDE: Find a Memorial Day service

- Log in to post comments