The secret history of Reds in Greene

By ANDREW MCGINN

Editor’s note: This story is being reposted in honor of the 60th anniversary of Khrushchev’s historic visit to west-central Iowa. It originally ran in April 2017.

The last time there was this much public distrust between Russia and America, the fried chicken and sugar-cured baked ham had to be tested with a Geiger counter before it was served at a luncheon in Khrushchev’s honor at the Coon Rapids farmhouse of Roswell Garst.

If you consume any amount of news these days, the general takeaways are likely to be:

• Russia is undermining democracy.

• We need more money for defense spending.

Welcome back to 1959!

Only this time, like the twist ending in an episode of “The Twilight Zone,” the president of the United States himself is suspect.

For his part, our 76-day-old commander-in-chief — a man whose second-favorite book after the Bible is purportedly his own, “The Art of the Deal” — says we have everything to gain by chummier relations with Russia.

His critics, on the other hand, are firmly convinced he’s something along the lines of “The Manchurian Candidate” — a plant that can be called on to do Moscow’s bidding.

However, the last time things between East and West went south, an unlikely group of citizens in an unlikelier place stepped up and helped save the world.

There’s no reason to believe Iowa and its residents can’t do it again.

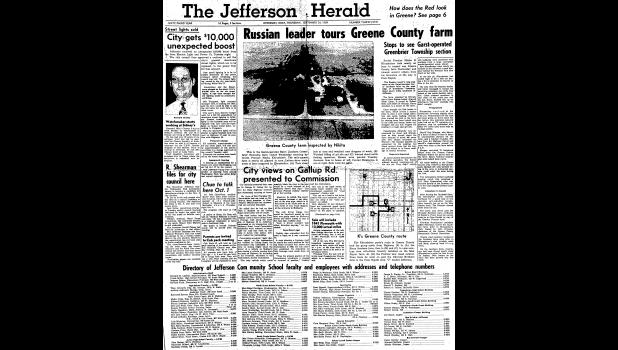

The state’s role in thawing the Cold War is today almost solely reduced to the Sept. 23, 1959, visit to Garst’s Coon Rapids farm by Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, his wife and their entourage.

It was a monumental moment in state history, to be sure — one that made the cover of Life magazine.

It also makes Coon Rapids a must-stop destination for Cold War-minded heritage tourists (like myself) on par with the nearby Strategic Air Command & Aerospace Museum outside of Omaha and the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site near the Badlands of South Dakota.

Today, Whiterock Conservancy stewards the Roswell and Elizabeth Garst Farmstead Historic District along Highway 141 in Guthrie County, which joined the National Register of Historic Places in 2009 — the 50th anniversary of Khrushchev’s visit.

What’s been largely forgotten is the part Greene County played in improving East-West relations at the height of the Cold War.

Even then to the national media covering Khrushchev’s visit, Iowa presumably looked like one big, continuous field of corn.

In reality, some of the most memorable moments from Khrushchev’s visit to Coon Rapids didn’t actually take place in Coon Rapids at all — they occurred in Greene County, according to reports of the day in the Jefferson newspaper.

To me at least, that’s an important distinction, and would be like saying something happened in Bulgaria when, in fact, it occurred across the border in Romania.

All I’m saying is that when it comes to one of the most famous moments in the history of Iowa, it’s high time Greene County gets its cut of the glory.

And had it not been for an earlier visit in the summer of 1955 to Jefferson by high-ranking Soviet agricultural officials, it’s very possible Garst never would have forged his unlikely friendship with Comrade Khrushchev that forever solidified the popular image of Iowans as common-sense, can-do people.

Sponsored by Iowa State College as an agricultural exchange, the 36-day trip to the Midwest in 1955 by a group of 12 Soviet officials — 12 Americans were permitted to visit the Soviet Union — was considered a breakthrough in international relations at a time when few in the West knew what lurked behind the Iron Curtain.

From the end of World War II until Stalin’s death in March 1953, the Soviet Union was pretty much the equivalent of North Korea today.

In that time, the Soviets exploded their first atomic bomb and fought a proxy war against the U.S. on the Korean peninsula.

Khrushchev would come to power with a policy of “peaceful coexistence” with the West, and was eager to develop a model of feed-livestock agriculture similar to our Corn Belt.

It would seem that if you’re a dictator, the best line of defense against your own people is first making sure they’re well fed.

That led Lauren Soth to write his now-famous editorial in the Des Moines Register — for which he later won the Pulitzer Prize — headlined, “If the Russians want more meat ...”

In it, he dared to invite Russians to Iowa to “see how we do it.”

“We promise to hide none of our ‘secrets,’ ” Soth wrote.

That was Feb. 10, 1955.

That July, against all odds, the Russians landed — a trip long since overshadowed in the annals of history by Khrushchev’s 1959 state visit.

WHAT IS THIS YOU CALL PINEAPPLE?

In retrospect, the speed with which Greene County extended an invitation to the Soviet ag delegation rivals only that of Russian tanks rolling into Hungary.

In a March 1955 telegram to U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Ezra Taft Benson, the county announced, “No place is superior to Greene County in the efficiency of its farmers, the hospitality of its people, the wealth of its soil, the excellence of its livestock and crops, and in the example it displays of the benefits which result from democracy in action.”

A group of six Soviets arrived in Jefferson on July 23, 1955, a Saturday, for a day and a half.

The other delegates went to Iowa Falls.

The purpose of the trip, from the Soviets’ standpoint, was to view the many services a community could offer to farmers, from grain elevators and machinery dealers all the way down to banks, schools and the newspaper.

In short, the Jefferson Herald reported on July 7, 1955, they wanted to “see how an average American small-town family lives.”

In an editorial published July 12, the Jefferson Bee acknowledged that not every resident was keen on demonstrating our way of life to visiting communists.

In other words, why let them wander around our Square when they have their own, Red Square?

“They (the opponents) are convinced that Russia’s food production has broken down,” the Bee wrote, “and that giving them ready access to American farm ‘know-how’ is giving ‘aid to the enemy.’ ”

“We cannot,” the Bee implored, “believe it is too late to give international good will a chance to operate.”

What ensued reads today like a trip to Earth by a group of six vacationing Martians.

The group began their visit to Jefferson in the home of Chamber of Commerce President Tom Cooper.

The Russians marveled at his freezer, his family’s store of canned goods, his water heater and softener, gas furnace, washing machine and drier.

They looked at the Ironite ironer with confusion, the Bee reported, “so Tom peeled off his shirt and the Mrs. demonstrated.”

That’s how foreign policy is done, folks.

From there they toured the high school, trying out the xylophone in the band room and attempting to shoot hoops in the gym.

At Jefferson State Bank, “they paused at the drive-in banking window before entering,” the Bee reported.

At Home State Bank, they stopped and had a Coke.

The pineapple at Safeway was a source of genuine interest, and they signed autographs wherever they went.

Makes you wonder how much an autograph is now worth by the chairman of a collective farm.

At the Oppenheimer and Durlam clothing store, it was reported that several of the Russians wanted sport shirts.

“One of the Russians was offered a bright pink shirt,” the paper reported, “but declined it. He wanted white.”

The fact that just one of them spoke English is probably the only reason they didn’t take in a showing of “Walt Disney’s Davy Crockett” at the Iowa Theatre.

And can we just talk about the fact that “Davy Crockett” was showing at the theater?

It perfectly completes the mental image of 1950s bliss.

On Sunday morning, they attended service at First Presbyterian Church in what the Bee called the most spectacular single event of the trip, as atheism was official Soviet policy.

There, they witnessed the baptism of one Kathleen Marie O’Neal.

But, as the paper noted, they didn’t sing or put any money in the collection plate.

Afterward, the Bee reflected on the visit, writing, “They did a public relations job which would put many American office-seekers to shame. We found ourselves watching to see if one of them would actually kiss a baby.”

To American war planners and the defense industry, though, the Cold War was never more than just one incident away from turning hot.

The same month — July 1955 — gave rise to a new term, the “bomber gap.”

That month at an air show in Moscow, the Soviets pulled off one of the great hoaxes of all time, repeatedly flying the same group of M-4 Bison bombers past the reviewing stands in order to give the illusion that they possessed mass numbers of jet bombers capable of delivering nukes to the United States.

The Americans fell for it, fearing the Soviets had more intercontinental bombers than we did.

Even the agricultural delegation’s successful good will trip — which also ventured to Nebraska, South Dakota, Minnesota, Illinois, Michigan and even California — was viewed with suspicion by officials in Washington.

“On balance the US-USSR agricultural exchange appears to have been to the Soviet advantage,” concluded a State Department intelligence report dated Oct. 17, 1955.

The Soviet delegates “gained quickly an enormous amount of information,” the report stated.

Officials conceded that the agricultural information obtained in the U.S. by the Soviet delegation was already freely available.

But they were nothing if not paranoid.

“Even if previously available,” the report warned, “US technical literature, by being illustrated in the field and supplemented with oral explanations, could thus acquire new meaning.”

A good time seemed to be had by all, but perhaps the Russians were just playing us.

After all, “Iowa nice” would sometimes seem to be a nicer way of calling someone gullible.

“Although the Russian delegation presents a front of complete amiability,” the Bee wrote after they departed, “it is well not to forget that all are top Communist party officials and their thought processes are not always the same as ours.”

Case in point: Their visit to the brick John Deere dealership of Charles Dunlop on North Chestnut Street (location of present-day Aureon across from City Hall).

The one delegate who spoke English, Alexandr Tulupnikov, a 46-year-old adviser to the Russian ministry of agriculture, asked Dunlop if the men in his shop were employed year-round.

Dunlop answered no, that two or three were laid off each winter.

Tulupnikov then turned to his comrades and, in Russian, translated what Dunlop just said.

His words were later relayed to the Bee via a Russian-speaking member of “Voice of America” who was present.

“In the winter,” Tulupnikov informed them, “they throw them into the streets like dogs. They have no work and must scavenge for their food and lodging.”

Nothing, thankfully, was lost in translation when Tulupnikov and another delegate broke off for a detour to the Roswell Garst farm near Coon Rapids.

There they found the one capitalist they could do business with.

HYBRID CORN FOR ALL

In Jefferson, the delegates had spent the night in the homes of three local families — the Lee Ausberger family, the Tom Cooper family and the Warren Garst family.

Founding president of Home State Bank, Warren Garst arranged for a quick, unofficial side visit to his nephew Roswell’s farm.

Before long, Roswell “Bob” Garst had an invitation to the Soviet Union, and by the dawn of 1956, had successfully negotiated the sale of 15,000 tons of Pioneer hybrid seed corn with Khrushchev.

The rest of the story has long since passed into legend.

In the version we know so well, thousands lined Highway 141 on Sept. 23, 1959, to see Khrushchev travel from Des Moines to Coon Rapids to visit the Garsts.

What has been lost to time are the details.

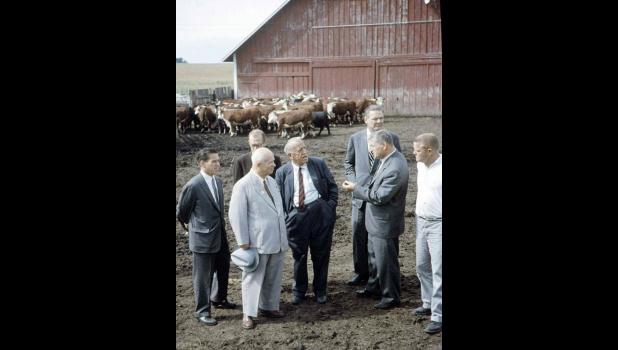

According to the Herald, the motorcade turned north from Highway 141 and shortly after 9:30 a.m. stopped at a Greenbrier Twp. farm operated by Harry Jacobsen on Garst’s behalf.

For nearly an hour, Khrushchev was on Greene County soil, inspecting Garst’s operation.

It was here, according to the Jefferson newspaper, that Garst flipped out on the more than 400 newsmen cramping their style, kicking and throwing silage at them.

The outburst became so well-known that at a festival in Coon Rapids in 2009 to commemorate the anniversary of Khrushchev’s visit, organizers held a silage throw on Main Street.

Silage, by the way, is fermented feed for livestock, and was being kept in an open pit 10 feet deep.

“At the silo pit,” the Herald reported, “Khrushchev just waded right in for a look not paying a bit of attention to swarms of flies in the air.”

When it came time to check out the cattle pen, Garst put son Steve on bouncer duty, who in turn threatened to “lay low” any reporter who didn’t stay clear, the local paper reported.

From the Jacobsen farm, Khrushchev’s motorcade surprisingly ventured even deeper into Greene County, making drive-by inspections of weed control, two new corn cribs on Max Naylor’s farm and other things before at last finally pushing on to Coon Rapids.

It remains an event well worth its umpteen retellings.

But going forward, it’s my hope we begin to place the Red where he rightfully belongs — in Greene.

- Log in to post comments