A PROFILE IN COURAGE

By ANDREW MCGINN

There’s a certain sense of futility when you begin giving mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to a man with a gaping hole in his cheek from where the fragments of a rocket-propelled grenade riddled his body.

It’s like trying your damndest to inflate a balloon with a rip in it.

Nick Friess nevertheless did what he could to delay what seemed inevitable, given the wounds.

By the time the helicopter touched down outside the hospital at Pleiku, in the rolling central highlands of Vietnam, Friess’ company commander was dead.

Neither Friess, an Army Green Beret medic who had graduated from Jefferson High School only 28 months prior, nor his 23-year-old captain were wearing dog tags, a sign that their work together was usually of the deny-or-disown variety.

But, curiously, Friess had no boots, either.

When the explosion unexpectedly rocked their Hatchet Force team of American commandos and indigenous Montagnard guerillas, Friess had been using a moment of downtime to inspect his trail-weary feet.

That day in 1969 — Sept. 26, to be exact — has remained with Friess every day for the past 51½ years. While it wasn’t the first death Friess attended to, and it wouldn’t be the last, the nature of it was one he has spent a lifetime trying to comprehend.

It was, Friess believes to this day, entirely preventable if only one of their own had been more caring.

Frankly, it would seem we’re up to our elbows these days in preventable deaths, having crossed a grim threshold of 500,000 COVID-19 deaths this week. The Associated Press on Monday reported that the rising COVID-19 death toll is now equal to the number of Americans who died at war in Vietnam, Korea and in World War II.

Combined.

If there’s another possible analogy between Vietnam and the current pandemic, it’s this: we got into both without a plan.

And just as our collective might was once stymied halfway around the world by a stone-age nation, so too has a virus, all of only 120 nanometers in size, been able to bring the most scientifically advanced people in history to their knees.

Arrogance can be a killer.

“Never ever underestimate your enemy,” Friess explained, “whether it’s the Viet Cong or COVID.”

Tragically, veterans have a higher risk of dying from COVID-19. Vietnam vets, in particular, are now of an age and suffer from pre-existing respiratory illnesses — brought on by exposure to Agent Orange — that puts them at very high risk for serious complications from COVID-19, according to the Veterans Healthcare Policy Institute.

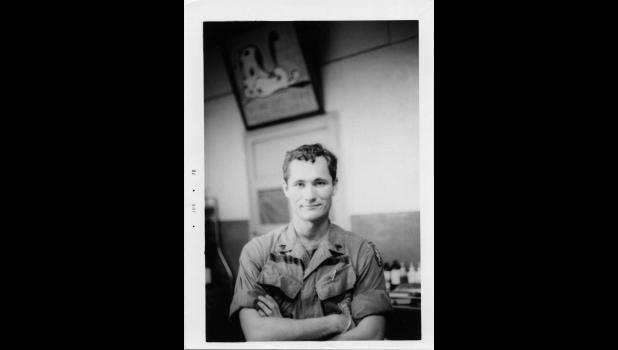

Now 72, Friess is living these days in the Pacific Northwest with his third wife, Laura. In his twilight, the Jefferson native is admittedly more content than he’s been in years following a decades-long struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). He also beat an aggressive form of prostate cancer made all the more likely by his own exposure to Agent Orange.

A form of therapy in his 50s known as prolonged exposure helped Friess finally gain the upper hand on PTSD, but he still does his part to keep his mind occupied, usually with art.

Long known for his paintings — dark still-life paintings that somehow always seemed to capture the essence of Vietnam without being about Vietnam — Friess has since discovered digital animation, tedious work that does his mind good and keeps intrusive thoughts at bay.

But the thing is, once you’ve seen death up close and often, you tend to place a greater value on life.

“You’re face-to-face, mouth-to-mouth, with this stuff,” Friess said, recalling his time in Vietnam with Army Special Forces. “You realize how extremely fragile the human body is.”

If anything sets Friess off these days, it’s the flippant way in which people confer the title “patriot” on one another, or that some regard going maskless in public amid a pandemic as courageous.

“Being courageous is caring about someone’s grandfather,” he said. “I am shocked by the lack of care and the lack of compassion.”

The country, Friess observed, now seems mired in what he called “nasty patriotism.” That nastiness — some would call it nationalism — is on full display daily on social media, and it came roaring to a head Jan. 6 when pro-Trump rioters besieged the Capitol hoping to overturn the results of November’s presidential election. Friess has undoubtedly seen more in his 72 years than most people, but he could have gone without seeing a 41-year-old guy from Arkansas using a flagpole to beat a D.C. Metropolitan Police officer on the Capitol steps.

“My worries aren’t about myself,” he said. “My concerns are about our society and our democracy.”

“It fills me with an intense rage,” he added, “which I can control. I am so pissed they keep using the word ‘patriot’ to describe these people. They have no idea what bravery or patriotism is.”

Friess actually considers himself to be middle-of-the-road on many issues. Right, left or centrist, he’s still entitled to his opinion like everyone else. But because he so blatantly put country before self in Vietnam — ultimately losing his left leg in the deal — it should be perhaps our patriotic duty to listen.

Fighting soldiers from the sky

I had asked Friess if he would be open to talking about his place in history after he recently shared a news story to his Facebook page about the highly classified U.S. unit in Vietnam — his unit — “that still influences modern special operations.”

Amazingly, two men from rinky-dink Jefferson — Friess and Bill Kendall — belonged to that same elite unit, MACV-SOG.

In longhand, they were both part of the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, Studies and Observations Group, which sort of sounds like their job was to go into the field and categorize the native flora and fauna.

Most times, the fauna shot back.

Kendall — much more on him in a second — passed away in 2018 at 83, having agreed to visit with me in 2014 for what became the most in-depth account in our hometown newspaper of his time abroad, in places of the world no “poor kid from the north side of the tracks,” as he called himself, belonged.

Kendall himself had always wondered “if the stories of the men who served in Vietnam will ever be told or appreciated,” as he lamented in a letter to the Herald in 2010, published on occasion of Veterans Day.

But while this is ostensibly another history story, also consider that we’ve now spent years arguing with one another about issues carried into a new century from a past that clearly isn’t even past. In fact, it seems that much of what has plagued our country these last few years stems largely from the unfinished business of the ’60s — and by ’60s, you can take your pick between the 1960s or the 1860s.

We’re still having the same old fights over equal rights, and about who or who isn’t worthy of being considered an American.

A good many of us are still strangely obsessed with the spectre of communism, assailing any and all social programs as a slippery slope toward Soviet-style thought control and breadlines. In the mid-20th century, those fears were reflected outward in the form of the domino theory — the idea that, should teeny places like Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia fall to communism, the whole world would end up toppling with them.

But maybe worst of all, we’ve rekindled an allegiance in the early 21st century to conspiracy theories right in keeping with those of the John Birch Society of the early 1960s, whose members once maintained that the ultimate goal of the civil rights movement was the creation of a “Soviet Negro Republic” in the American South.

“It’s all come together at the same time,” Friess observed.

Friess now resides near Sequim, Wash., a town not that much larger than Jefferson that has attracted national attention as of late because of its mayor’s expressed support for QAnon, the far-right authoritarian cult founded on the belief that Democrats are satanic pedophiles.

“Most of us knew it was always out there, but it was always on the fringe,” Friess said of conspiracy theories.

Seeing friends and acquaintances get caught up in it “has been the shock,” Friess said.

Perhaps it’s Friess who has changed.

As a kid, he grew up on East Madison Street in Jefferson across from Randy Weaver, who would later gain infamy during an 11-day standoff with federal agents at Ruby Ridge in Idaho.

What happened at Ruby Ridge in 1992 was beyond tragic — Weaver’s wife, Vicki, was killed by an FBI sniper — but he had come to harbor white separatist beliefs.

As kids, Friess remembers the day they both wanted to impress a girl named Lana. Weaver had a pair of boxing gloves; Friess had a book about jujutsu. In separate bids to impress Lana, each asked the other to take a beating.

As Friess and Weaver were busy decking one another on someone’s front lawn, Lana walked right on by, oblivious to either.

Weaver would eventually graduate with the JHS class of 1966; Friess with the class of ’67.

Unbelievably, both ended up making the cut as Green Berets at a time when “The Ballad of the Green Berets” was a No. 1 pop hit.

Even though Weaver remained stateside, what were the odds? And, beyond that, what were the odds that at least three Jefferson men would simultaneously don the iconic green beret? Weaver and Friess joined Kendall, a 1954 graduate of Jefferson High School who had gone on to become one of the nation’s first Green Berets, even though no one at the time really knew what that meant.

It meant that when Weaver and Friess were still at the pink-hued elementary school in Jefferson, Kendall was already kicking supplies out of a transport plane over Laos for the Royal Lao government to use in its fight against a communist insurgency known as the Pathet Lao.

The fight in Laos would outlast them all. Kendall and Friess were once again civilians in Jefferson when the Pathet Lao took control of Laos in 1975.

Later on in the ’90s, Friess reconnected with Weaver when he resided in Grand Junction under the conditions of his probation following Ruby Ridge.

When the talk drifted to politics and religion, the boys who grew up across the street from each other were now miles apart.

“He looked at me and said, ‘You’re never gonna see this, are you?’” Friess said, recalling how they were civil toward each other afterward but never the same.

Fearless men who jump and die

For Friess, the Army presented itself as an option of last resort. He had already dropped out of Iowa Central Community College and was failing in his attempts to meet quota on the boning floor of the pork plant in Perry when he decided to enlist.

His performance on the Army’s aptitude test suggested he might have the makings of a Green Beret, the name given to members of Army Special Forces since 1962, when President John F. Kennedy made their distinct headgear official. The first unit had been established in 1952 under the U.S. Army Psychological Warfare Division, and members began distinguishing themselves two years later by donning green berets.

In Vietnam, Green Berets who volunteered for duty with MACV-SOG — officially activated in 1964 as the precursor to today’s joint special operations units — sometimes ran programs for the CIA but above all answered only to the Pentagon.

They descended into the jungle just a few at a time, accompanied by the tribesmen-turned-guerillas the old colonial masters had named Montagnard, French for “mountain man.” Together they performed harrowing acts of sabotage, reconnaissance, counterintelligence, psyops (short for psychological operations) and, when needed, direct action.

Against the advice of buddies who were absolutely sure he’d be killed, Friess volunteered for duty with MACV-SOG upon arrival to Vietnam in August of 1969. That September, he made his way to Kontum in the central highlands, home to MACV-SOG’s CCC, or Command and Control Central, which operated clandestinely in southern Laos and northern Cambodia — places supposedly off-limits to American forces.

Friess would eventually find the secrecy unsettling, and especially unbecoming of a nation that looks on itself as the beacon of democracy in the world.

“I was starting to have misgivings about doing some things the American public wasn’t allowed to know,” Friess said, explaining how he came to leave MACV-SOG for duty at a hospital in Can Tho set up by Special Forces to care for the Montagnard as part of the effort to win their hearts and minds.

Later, in March of 1970, Friess would be wounded on the 10th day of a 10-day mission in the Mekong Delta. The wound would fester for decades, resulting in the amputation of his left leg at mid-calf in 1992.

But that day in 1969 when Friess first arrived at Kontum, the welcoming committee couldn’t have been more unexpected.

“Here I am,” Friess said, “halfway around the world and this guy comes over to me, says, ‘I heard you’re from Iowa.’”

It was Bill Kendall.

Standing there together in the heart of darkness, the two guys from the heartland could hardly believe it when Kendall asked the obligatory, “Where in Iowa?”

“We just kind of looked at each other and went, ‘What the hell?’” Friess recalled with a laugh.

Until then, Friess only knew of Kendall and had heard some “vague stories” about this guy from town who’d gone to Vietnam and come back. Friess had obviously no idea that Kendall was, in reality, an old hand at black ops, or that he’d returned to ’Nam.

Kendall at that time had just two and a half weeks to go at CCC, and ran his own tight-knit recon team, so the two Jefferson natives never worked together.

Friess was attached to a larger, company-sized unit of Americans, Vietnamese and Montagnards. His first mission was to be a 10-day excursion to scout the infamous Ho Chi Minh trail, the route that kept communist forces in South Vietnam supplied by North Vietnam. To the irritation of American commanders, the trail snaked in and out of two other countries, Laos and Cambodia.

Nevertheless, the U.S. had been taking aerial photos of the trail and trying to bomb it into oblivion since 1964, when all that stuff was still secret. Still, the dense jungle canopy required boots on the ground to determine its true twists and turns.

“I thought it was going to be one flat swamp,” Friess said of Vietnam. “The central highlands are like the Black Hills. The country is beautiful in places.”

Friess was on the fourth helicopter to enter the LZ, each inserting its killer cargo of men with no identifiable markings save for the color of their Yankee skin.

“The fifth helicopter,” he said, “crashed.”

It was Sept. 20, 1969, and Friess made it his first act of his first mission to help free a man pinned underneath the wreckage of the downed H-34 Kingbee.

It was just the beginning of what would be a 10-day baptism by fire, with Friess as the company medic trying to keep up with first aid as soft tissue was blown apart all around him.

It was during a lull in the fighting when Friess decided to slip off his boots and check his feet.

It was then that a fellow Green Beret emerged from the bush with the warhead from a captured rocket-propelled grenade, tossing it into the air and catching it like he might a baseball. It disturbed Friess to see this Green Beret, whom he didn’t know, playing so casually with something that could so easily kill them both. Friess told him as much, but the soldier only taunted Friess as a chicken.

Friess nevertheless stood his ground, and the soldier walked on.

And then it happened. An explosion.

To this day, Friess is certain the soldier’s toy RPG round detonated. The soldier was sprayed with fragmentation, but unbelievably lived. Their company commander wasn’t as lucky.

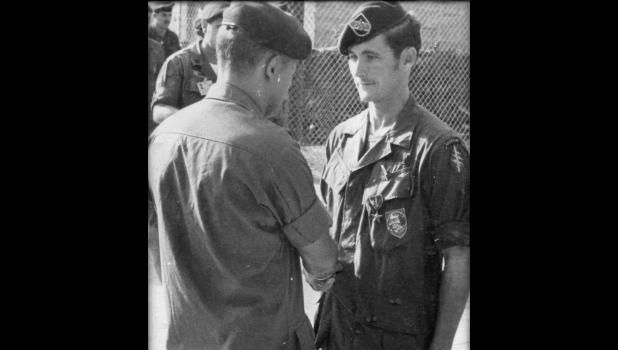

For his efforts over six days, Friess was awarded the Bronze Star, but the medal and its jargon-heavy citation rang hollow.

The award became the stuff of Page 1 local news that November, when the Herald ran the citation in full. “For heroism in connection with ground operations,” it read in part, “against a hostile force in the Republic of Vietnam.”

That was a lie.

On two fronts, really.

One, they were in Cambodia. And two, at war as in peace, we are often our own worst enemy.

Friess knows the value of life.

He’s seen the bravest of men mangled, while others died with a simple hole in their chest.

“It is so easy to kill someone,” he said. “What’s hard is caring for people.”

- Log in to post comments