Now pitching for Churdan: Bob Feller?

By ANDREW MCGINN

There’s something about a throwback baseball jersey that’s just so cool, from the styling of the team’s name to the sometimes weird combination of colors (looking at you, Houston Astros jersey from the late ’70s and early ’80s, with your “rainbow” stripes of orange, red and yellow).

There seems to be no end to the number of old-school jerseys out there for sale.

One company specializing in replicas of pre-1970s wool jerseys prides itself on historical accuracy, and if you’re the discerning hipster (or baseball wonk) who wants to rock the most obscure jersey ever, take your pick from any number of Negro league teams, old farm squads and even Japanese franchises.

How about a 1929 Des Moines Demons home jersey?

Personally, I think it’d be cool to represent the Japan Central League.

I’ve got my eye on the road jersey donned in 1953 by the Hiroshima Carp. Or else the Sankei Atoms’ 1966 home jersey, primarily for the sleeve patch of the Japanese anime icon Astro Boy.

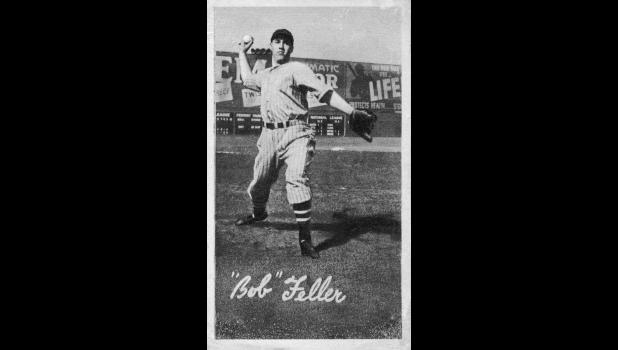

But there’s still one throwback jersey that would lay waste to all others in terms of obscurity if they made it (which is precisely why they need to make it) — Bob Feller’s Churdan Cardinals jersey.

Yes, I’m referring to the late Hall of Fame pitcher who’s still the greatest Indian of all time (apologies to Red Cloud, Sitting Bull, Chief Joseph or Tecumseh).

Just 19 months after suiting up for Churdan in 1935, Feller was on the cover of Time magazine.

If you’ve never heard of the Churdan Cardinals, you’re probably not alone. They were the town team for a few years during the Depression, when semipro townball upheld baseball’s reputation as the national pastime.

Jefferson had the Merchants. Carroll had the Firemen.

This weekend marks not only the end of summer (autumn begins Sunday), but the final weekend to experience “Hometown Teams: How Sports Shape America” at the Greene County Historical Museum.

It’s a perfect time, then, for one last tale from baseball’s golden age — and I’m almost willing to bet you’ve never heard this one before.

Presented locally by Jefferson Matters: Main Street and the Greene County Historical Society, “Hometown Teams” — a traveling exhibit of the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum on Main Street program — opened Aug. 11 in Jefferson, and has been seen by more than 1,900 people as of Sunday.

The biggest draw hasn’t actually been anything that traveled here from the Smithsonian, but rather the informal displays of uniforms and trophies saluting the sporting legacies of Rippey, Grand Junction, Cooper and other local towns.

Baseball, it should come as no surprise, looms large throughout.

From Paton and Rippey to Yale and Bagley, no town in the area was without its own semipro ball team, and sometimes even two.

In Churdan, the Cardinals gained an “inter-city rival” — the actual words used by the newspaper — when the Churdan 4C’s (short for Churdan Cedar Catholic Community) entered the fray in 1939.

Today, there might not be enough young guys in these rural communities to put together so much as a bowling team.

And their names! Practically every one sounds like it belongs to the cornfield at the Field of Dreams.

The Jefferson Merchants boasted star pitcher Lefty Marlenee and second baseman Bum Peterson, a slugger who batted .450 in the summer of ’34.

The Cardinals were managed by Spike Conant, who was apparently so disgusted by his team’s dismal performance in the summer of ’36 that he canceled their remaining schedule.

That summer — 1936 — was the summer Bob Feller, the hard-throwing wunderkind from nearby Van Meter, made his big league debut with the Cleveland Indians, smoking 15 hapless St. Louis Browns (the present-day Baltimore Orioles) in a single game on his way to embarrassing the Philadelphia A’s, 17 of whom were unable to get so much as a piece of his soon-to-be-legendary, 98.6 mph fastball.

At just 17, Feller was the only kid in America who could say he spent his summer pitching against Joe DiMaggio, Lou Gehrig, Hank Greenberg and other greats. In fact, he still had one year to go at Van Meter High School.

Feller was already well known in neighboring Greene County, where man after man in the summer of ’35 tried and failed to save face while staring down the 16-year-old kid who threw for the Farmers Union amateur club of Des Moines with a funny, high kick.

In one game against the Churdan Cardinals, Feller struck out 18.

He was averaging 19.4 strikeouts per game that summer, and achieved the first no-hitter of his life against Yale, striking out 22.

“The three (no-hitters) I pitched for the Cleveland Indians were great thrills,” Feller would write in his 1990 autobiography, “but this first one was just as big a kick.”

The boy wonder

A Labor Day rematch at Spring Lake between the Cardinals and the Farmers Union team was to be a highlight of the annual Greene County Farmers Union picnic.

National labor leader Milo Reno, whose Farmers Holiday Association wanted farmers to be paid for the actual cost of production, took the occasion to assail new federal farm subsidies in exchange for reduced production in a speech echoing today’s mantra of “trade, not aid.”

The speech inspired what surely has to be one of the all-time greatest Page 1 headlines in Jefferson newspaper history: “Reno Says Farmers Were Given ‘Sugar Tit’ to Keep Them Quiet.”

The Cardinals later played like they were in a diabetic coma — losing 11-2.

Feller fanned seven batters in three innings.

“The kid is a wonder,” the Herald raved. “He has speed and curves and throws easily, too.”

The paper heralded Feller as “one of the most outstanding young pitchers discovered for a long time,” noting that he was being pursued by big league scouts. The Detroit Tigers seemed to be particulalry anxious to court the Dallas County farm boy.

In reality, although nobody knew it yet, Feller was already a big leaguer.

He had signed in secret July 22 with the Cleveland Indians for all of $1 and an autographed ball.

It was Cedar Rapids native Cy Slapnicka, a freewheeling scout for the Indians, who got to Feller (and his dad) first, and it meant trudging out into the family’s wheat field near Van Meter, suit coat slung over his arm, to do it.

The contract was kept a secret so that Feller could continue playing sports in high school.

Well, that, and it was specifically against baseball’s own rules for a major league team to sign an amateur player directly.

Technically, Feller was signed by “Slappie” to the Indians’ Class-D farm team in Fargo, the Fargo-Moorhead Twins, but it was clear he was never meant to so much as visit Fargo.

With Feller soon laying waste in the majors to men twice his age, tough-as-nails league commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis — the guy who had banned Shoeless Joe Jackson and the other “Black Sox” from the game for life for throwing the 1919 World Series — launched an investigation after a complaint from Lee Keyser, owner of the aforementioned Des Moines Demons, a minor league team.

Feller got to stay with the Tribe, Landis ruled, but the Indians had to fork over $7,500 to Des Moines for plucking an amateur from their recruiting area.

All the Churdan Cardinals knew in September 1935 was that they clearly couldn’t beat Feller — so why not just hire him?

The use of ringers was commonplace in those days, and on Sept. 5, 1935, Feller suited up as a Cardinal for their game against the Jefferson Merchants to open that year’s Greene County Fair.

For its part, Jefferson imported the three Lindgren boys of Paton, putting Paul Lindgren on the mound.

Frankly, though, when you’re talking about Bob Feller, Mrs. Lindgren could have birthed nine boys and it wouldn’t have mattered.

As Hall of Fame manager Bucky Harris would later tell his Washington Senators when facing Feller’s fastball, “Go on up there and hit what you see. If you can’t see it, come on back.”

Feller “whiffed 18 batsmen,” as the newspaper put it, and led Churdan to a 3-2 win over Jefferson.

This is one of those stories that has circulated in my family for years.

My Grandma Virginia’s second husband, Roy Mosteller, was a member of the Churdan High School class of 1925 and played right field for the Cardinals.

I first heard of Roy playing against Bob Feller around the time I was heavily into baseball cards as a kid.

As I grew older, I began to wonder if Roy really did, in fact, go up against Feller — or did every guy of a certain age in this area make the same claim?

The story has “rural legend” — “urban legend” just doesn’t seem to fit — written all over it, despite a passing mention of Feller being hired to pitch for a Churdan team in a book published back in 1982 to commemorate the town’s centennial.

The book offered no specifics, making the story easy to forget.

The story even slipped past Paul White, Churdan’s resident historian.

“And I was on the committee that put the book together,” he said recently.

In my first attempt at research, I struck out.

I found a December 1938 blurb in the Herald about Feller, his brother and two young ladies dining at the Hotel Lincoln in Jefferson — Feller had just set major league baseball’s modern strikeout record that October — but little else of interest.

Well, aside from a game the Churdan Cardinals were to play in August 1934 against the “Mahatma Ghandi nudist base ball club.”

I have no idea who or what they were, but when you read that a “nudist base ball club” will, in the words of the paper, “cross bats with the Churdan Cardinals,” your mind really takes off.

Even with the digitization of Jefferson’s newspaper archives, you won’t find the story of Bob Feller pitching in Greene County.

That is, unless you misspell his name like the local newspaper did.

For a solid year, he was “Bob Fellers” in the pages of the Bee and Herald.

“Bob Fellers to play with Cleveland Indians,” the Herald reported on June 25, 1936, one last goof before the whole world would come to know his name.

The next year, NBC Radio covered his graduation from high school in Van Meter.

Feller, who died in 2010 at age 92, went on to pitch for the Indians until 1956. Giving up nearly four seasons to man an anti-aircraft gun on the USS Alabama during World War II — the first major leaguer to enlist — he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame alongside Jackie Robinson in 1962.

Feller would have turned 100 this fall (Nov. 3 to be exact). Grandpa Roy would now be a spry 112 himself.

I wish I could wear a Churdan Cardinals throwback jersey to celebrate.

Complete with “Fellers” on the back.

- Log in to post comments