A longer shelf life.

By ANDREW MCGINN

a.mcginn@beeherald.com

Melchior Huebinger was not messing around.

When you get to page 4 of his “Pocket Automobile Guide for Iowa,” it’s hard to miss his warning to anyone caught monkeying with the book’s contents.

“I have complied with the requirements of the copyright law,” reads the sternly worded message from Mr. Huebinger, “and any infringement in whole or part will be prosecuted.”

The penalty, he warns, will be prison for up to a year or a fine “not less than one hundred dollars nor more than ONE THOUSAND DOLLARS, or both, in the discretion of the court.”

Janice Harbaugh doesn’t really look like you might expect an intellectual property thief to look like.

A silver-haired retiree and a lifelong lover of books with a cat named Mr. Hobbes, the fifth-generation Greene Countian nevertheless obtained a copy of Huebinger’s book at a flea market, scanned every one of its pages onto her home computer and is now reselling it.

Willful infringement?

Without question.

Gleeful even.

But Harbaugh is well within the law.

In fact, without her efforts, Huebinger’s books — yes, books, plural — would have long been forgotten by now.

“I find the copies that are left,” Harbaugh, 68, explained recently.

Because it was originally published in 1915, “Huebinger’s Pocket Automobile Guide for Iowa” is in the public domain, that realm within the intellectual property law cosmos where books and films wind up when their copyright protection lapses.

In retirement, Harbaugh has become a publisher of rare books that have been exiled in the public domain.

Through her Raspberry Ridge Publishing imprint, the Jefferson resident has revived books on early Iowa auto travel and the marvels of modern science (as of 1920, that is).

There’s a book from 1904 titled “Iowa Laws Made Plain” and a 1918 book, “The World War at a Glance,” that explores World War I clear down to the national debts of the belligerent countries.

Harbaugh also has collected century-old postcard art into e-books, and she has a line of reproduction postcards of local interest available at the Bell Tower and at Wild Rose Casino and Resort.

A local postcard from 1910, titled “State Street on Circus Day, Jefferson, Iowa,” depicts a circus parade making its way down what was then still just a dirt road. The buildings, however, are immediately recognizable.

“I’m looking forward to RAGBRAI to sell postcards,” Harbaugh said.

As far as retirement hobbies go, hers is easily among the more unique.

“When you retire,” she said, “you just open up to life.”

“Retirement,” she added, “just opened this creative phase of my life.”

Sure, a lot of people love to hunt for antiques in retirement, but Harbaugh has taken it a step further, scouring antique shops, flea markets and eBay for books lost to time that she feels deserve a second life.

“Once you do one, you’re just hooked,” she said. “It’s one after the other. You always find something else you want to do.”

Harbaugh’s reproductions are quite often the only way of accessing the original source material.

“None of this sells a lot,” she confessed. “It’s niche publishing.”

Her reproduction of “The Great Quadrangular Debate: Philadelphia 1893” isn’t likely to make anyone’s top 10 list of favorite books, but it could be a boon to scholars of Iowa politics and presidential elections.

At the time of its original publication in the 1890s, the nation’s political parties were all vying for the heart and soul of working-class America as the country evolved from an agrarian society to an industrial one.

Four-way debates were held between Republicans, Democrats, a third party and a member of the clergy.

James Baird Weaver, of Iowa, was given the honor of representing the Populist party in Philadelphia. A two-time third-party candidate for U.S. president, Weaver had actually managed to snag some electoral votes in the election of 1892.

Harbaugh admittedly has to be personally interested enough in the subject matter to scan, in some cases, hundreds of pages.

But what fascinates her is trying to figure out what in turn fascinates someone else to buy, say, the 1920 edition of “Collier’s Wonder Book” (make that the 2013 Raspberry Ridge Publishing edition) of scientific marvels.

“It’s meaningful to them in some way,” Harbaugh said. “Something just clicks. That’s what fascinates me.”

Her reprint of the Greene County Culture Club’s 1900 cookbook surprisingly doesn’t sell many copies here at home, but at least once a month, someone in England orders a copy.

She has no clue what draws the British to a cookbook produced by the local women’s club at the turn of the century featuring Mrs. Benjamin F. Jaques’ recipe for “pork cake” (“warranted to keep for six months,” Mrs. Jaques noted) along with a selection of advertisements for Jefferson businesses.

“Some day,” Harbaugh said,

“I may find out.”

That’s sort of the mysterious beauty about selling books exclusively through the internet.

“You throw out something to the universe,” she said, “and you never know what you’re going to get back.”

Harbaugh works with CreateSpace to make her library of books available through Amazon.

CreateSpace prints each title on demand, and also takes care of shipping.

The first book Harbaugh ever reproduced, 2011’s “The Production Packard: A Restoration Reference,” remains her top seller, selling a couple of copies every month.

“If someone wants to restore a Packard,” she said, “this is the book. This is every nut and bolt.”

For a more general audience, though, “Collier’s Wonder Book” makes for delightful reading, and is a must for retrofuturists.

Some of its entries are downright prophetic, particularly the chapter predicting that atomic energy could one day supplant oil and coal as a power source.

But even as far back as 1920, scientists feared they could be unleashing something unspeakable on the world.

“I hope that the human race will not discover how to use this energy until it has brains and morality enough to use it properly,” Sir Oliver Lodge said of atomic energy, “because if the discovery is made by the wrong people this planet would be unsafe.”

Sir J.J. Thomson went on to predict the atomic bomb: “In fact, the explosion of the atoms in a few pounds of material might be sufficient to shatter a continent.”

Of course, for every chapter in the “Wonder Book” on actual scientific achievements, there are chapters with titles such as, “Do Spirits Talk Through the Ouija Board?”

“When I’m working on a book,” Harbaugh explained, “I’m imagining someone from that time and how I might have used that book.”

There’s no question how someone might have used Huebinger’s series of Iowa travel guides.

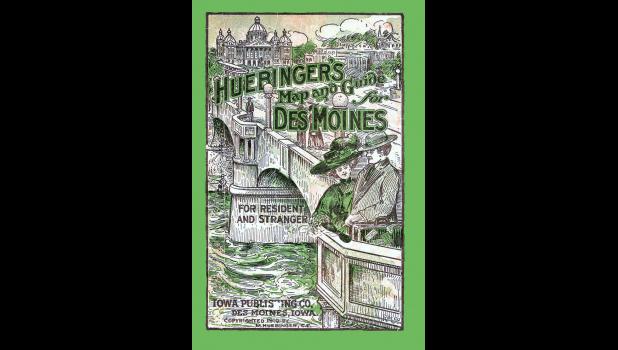

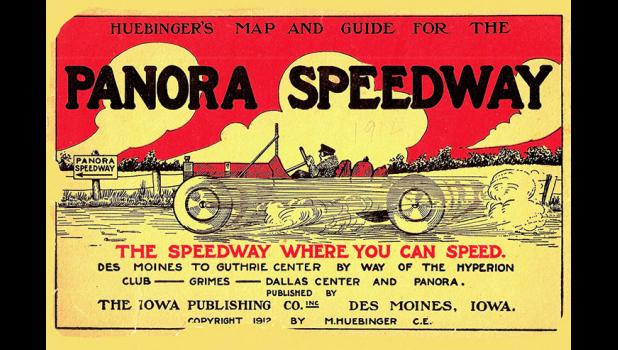

Of local interest will be “Huebinger’s Map and Guide for the Panora Speedway” and “Huebinger’s Map and Guide for Des Moines, Fort Dodge, Spirit Lake and Sioux Falls Highway,” both originally published in 1912.

An immigrant from Germany, Huebinger settled in Davenport to become the state’s preeminent surveyor and map maker.

His 1904 atlas of Iowa, containing 360 pages and 99 plates, was the first of the state since 1875.

In the early days of motoring, the Panora Speedway was a straight shot from the Hyperion Club in Des Moines to Panora, at which point it went north to Jefferson or continued on to Guthrie Center.

“You could go as fast as you wanted,” Harbaugh said. “They called it the speedway where you could speed.”

At Panora, the speedway featured a spur north to Jefferson and the transcontinental road.

Huebinger’s guide to the Des Moines, Fort Dodge, Spirit Lake and Sioux Falls Highway offers up a compelling argument for why highways should be numbered rather than named.

But in 1912, the highway with the ridiculously long name took travelers on a direct route from the state capital to the Iowa Great Lakes by way of Grand Junction, Dana and Paton.

“It’s fun to go for a drive and follow these old maps and see what’s still there,” Harbaugh said.

Landmarks near Paton identified on Huebinger’s map include, no joke, “unpainted house” and “stumps.”

Huebinger eventually died at age 69, apparently the result of an infection caused by an ill-fitting shoe.

The year of his death — 1923 — has for 20 years served as the dividing line between works in the public domain and works still potentially protected by copyright.

“Copyright law is incredibly complex,” Harbaugh said.

Here’s basically what you need to know: Anything published in the U.S. before 1923 is fair game for public use, meaning it’s no longer protected by copyright.

Everything else, you better be prepared for an exhaustive search of copyright filings and renewals.

It’s a poorly kept secret that every so often, Disney persuades Congress to extend the length of copyright protection, keeping Mickey Mouse (created in 1928) from falling into the deep, dark clutches of the public domain.

That means it could be a while yet before Harbaugh gets to publish her own version of 1931’s “The Adventures of Mickey Mouse,” Mickey’s first storybook. Even then, Mickey might still be protected by a trademark.

It’s confusing, to say the least.

But a series of children’s books by author David Cory chronicling the adventures of Puss in Boots Jr. is fair game for Harbaugh.

She was drawn to Cory’s witty writing.

She so far has reprinted eight of Cory’s 10 Puss in Boots Jr. books published between 1917 and 1921.

Harbaugh has long known the power of books on children, in particular.

In her work as a therapist, she employed bibliotherapy, in which kids are able to identify with the characters in a book.

“I know what effect those characters had on me,” she said.

Growing up near Herndon on the Greene-Guthrie County line, Harbaugh personally identified with Nancy Drew, the fictional teenage detective.

She once wanted to be a detective just like Nancy Drew — and in a way, she actually became Nancy Drew, testifying for the state in a criminal sexual abuse case in Jasper County in 1991.

That case marked the start of a relationship with the Iowa Department of Human Services, working until her retirement in 2009 with foster kids who had been physically, sexually or emotionally abused.

Harbaugh’s own book, “Captain Duffy and the Kid Who Threw Eggs,” about the emotional journey of a foster child, has long been used by counselors.

She attributes her love of writing to an unlikely person: Bruce Towne, the man who ran Jamaica’s grocery store when she was a girl.

Towne published his own newspaper, Towne Talk, that he would stuff in everyone’s grocery sack, Harbaugh said.

Harbaugh was a fourth grader at Jamaica Elementary when Towne printed a poem she wrote. It was the first inkling Harbaugh had that she might actually be a writer at heart.

Towne in 1957 also authored what’s considered the definitive history of Jamaica, “Bricks on the Chimney.”

“There’s not a lot there now,” Harbaugh said, “so people don’t realize what used to be.”

Six decades later, using a copy of the book found on eBay, “Bricks on the Chimney” is about to get a new printing thanks to Raspberry Ridge Publishing.

“It’s come full circle,” Harbaugh said. “He started that thought process that maybe I could write. Now I’m going to reprint his work.”

“This is my way to give that back to him,” she said, “60 years later.”

- Log in to post comments