Hip artist, square job

By ANDREW MCGINN

a.mcginn@beeherald.com

In my mind, I’m picturing John Beardsley in the gray winter of 1962 dropping Ornette Coleman’s new record, “Free Jazz” (the one with a Jackson Pollock painting on the cover), onto the hi-fi, taking a hit of Benzedrine and then, with his bare hands covered in blue and yellow paint, moving them around the 20-foot-long canvas to the sound of Charlie Haden’s bass solo.

Maybe there’s a dog-eared copy of Kerouac’s “On the Road” on an end table somewhere. Or maybe “On the Road,” after five years in publication, is already a golden oldie. So maybe instead there’s a copy of Robert Heinlein’s new science-fiction novel, “Stranger in a Strange Land,” lying about.

There’s definitely a haze of smoke.

What kind of smoke, I can’t say for sure.

Let’s just say no one has ever painted a Greene County farm scene quite like this before, or since.

Beardsley would complete two paintings that winter, each of them on display to this day in the rotunda of the Greene County courthouse.

Greene Countians marked the centennial of the courthouse Friday with an observance exactly 100 years to the hour — how’s that for detail? — that the building was dedicated on Oct. 27, 1917.

It goes without saying, but not every county has a courthouse like ours. Growing up here in Jefferson, I assumed they did. Only later in life did I come to realize that to find a comparable courthouse, what you really need to do is look to state capitols.

Part of what makes Greene County’s courthouse so magnificent — aside from the fact that it’s been meticulously cared for all these years — is the art.

It was mentioned Friday at the Courthouse 100 event that, a century later, we still don’t know why the building’s architects included so much artwork. And of the art, we know so little about the artists.

The identity of the artist responsible for the spectacular ceramic mosaic on the rotunda floor, in particular, remains a mystery on par with what happened to Amelia Earhart’s plane.

We do know the names of the two painters responsible for the four murals around the stained glass dome that depict a sort of people’s history of Iowa, from immigration and sod houses to modern-day farming.

William Peaco, of the Andrews Decorative Co., was originally responsible for all four.

By January 1962, water seeping in through the dome had managed to pry one mural from the wall, damaging it beyond repair. A second mural had water damage and was about to fall.

That’s when this cat, Beardsley, who just happened to be living in Jefferson at the time, was recruited to paint two new murals.

Beardsley is often characterized as simply just a “local artist.”

The truth is, he was a lot more interesting than we ever really knew.

By the time Beardsley died of cancer in the ’80s, his work had been scooped up by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Actors Steve McQueen and Raymond Burr owned his pieces, as did novelist Norman Mailer.

Fellow painters Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline owned his work as well.

Beardsley was a part of the same abstract-expressionist movement that had shifted the modern art capital of the world from Paris to New York following World War II.

This was the era of “action painting,” when drips, streaks and smudges were frenetically applied to canvas and masonite in substance-enhanced bursts of creativity.

Not long after Beardsley moved to Jefferson in late 1961 with his wife, the former Janet Nunn (Jefferson High Class of ’50), and two little daughters, local newspaper columnist Mary Kay Kidder paid him a visit.

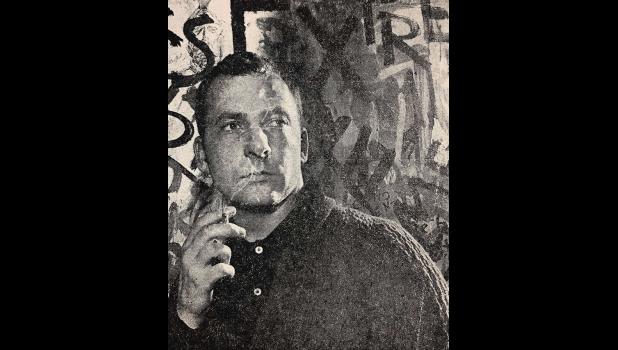

Her column carried a square title — “Diary of a Housewife” — but Mary Kay proved to be quite hip. She knew a cool story when she saw one, and a photo accompanying her Jan. 16, 1962, column in the Jefferson Bee shows Beardsley at work in his basement studio on a giant painting of Christ’s crucifixion (a familiar theme throughout his life) with just his hands.

He seldom used brushes, she reported.

How’s that for action painting?

At the time, Beardsley was also preparing to be the subject of a one-man show in New York City.

Beardsley was the real deal, and I can only imagine his conversation with the county about painting two bucolic farm scenes for the courthouse.

Here was an abstract-expressionist — a guy on the front lines of the avant-garde — being asked to essentially produce two very traditional pieces of art, recognizable forms and all.

“I wouldn’t say it was his best work, but it’s unique,” said Amy Goodale, a daughter born to Janet Nunn and John Beardsley in 1964, after they’d already left Jefferson.

Nunn and Beardsley would eventually divorce, in large part because of his alcoholism, Goodale said.

Goodale can now see the various drugs of the era — as the beat movement gave way to hippiedom — in her dad’s paintings.

Goodale accompanied her mom home several years ago, paying a visit to the courthouse.

It would prove to be Janet Nunn’s last trip home. She was Janet Goodale when she passed away this past April in Raleigh, N.C., from cancer and dementia at age 84.

Amy Goodale, who owns a firm in downtown Raleigh that designs and builds historic-inspired homes, suspects her dad probably painted at least part of his two murals with his hands. That, she explained, was a technique he explored for a short time.

He most likely painted the murals using brushes.

“He had a magnificent eye for color,” Goodale said. “We were shocked to see that it was still there and hadn’t been painted over.”

By newspaper accounts, the family only lived in Jefferson for about a year, but it just happened to be at a time when Greene County found itself in need of a muralist.

“He did stand out in that community,” Goodale said of her dad.

An Onawa native and the son of an attorney, Beardsley was as bohemian as they came.

As an art student in 1959 at the University of Iowa — then known as the State University of Iowa — Beardsley was a lefty who dug philosophy, politics, creative expression and European coffee.

That’s what they would have called a beatnik here in Jefferson.

As a student, he was the proprietor of Renaissance 2, Iowa City’s first coffeehouse and “the new rallying point for many SUI leftbankers,” as the Daily Iowan put it in February 1960.

It was the kind of place inhabited by poets, painters, actors, writers and jazz musicians.

We can only assume there was a ton of finger-snapping going on.

Naturally located above a bookstore, The Paper Place, it was a little slice of Greenwich Village or San Francisco’s North Beach right there in Iowa City.

Beardsley had brought the idea back to Iowa from Los Angeles, where he studied at the Los Angeles County Art Institute.

The turntable in the Renaissance 2 hi-fi room never stopped spinning, and probably not with teenybopper records.

Rather, this was a place where one could lay around and listen to a spoken-word recording of Pamela Brown reading “Lady Chatterley’s Lover,” the 1928 book that was the “Fifty Shades of Grey” of its day and the subject of an obscenity trial in the U.K. in 1960 (Penguin Books successfully defended itself).

Beardsley, who had an anti-authority streak in him, naturally gravitated to abstract-expressionism because “at the time it was breaking the rules,” Goodale said.

It would take him a while, and it would ultimately cost him a marriage, but Goodale said her dad would eventually learn to reconcile the two worlds — the straight world and the hip world.

He lived the final years of his life sober, telling a Florida newspaper shortly before his death, “When I gave up drinking, I felt a sense of rebirth, a psychic rearrangement and a sense of hope.”

Oh, though, to be a fly on the wall that winter he painted the two murals for the courthouse.

- Log in to post comments