A GOOD WHITE FOOL

By ANDREW MCGINN

The only image of Jesus that Dale Hanaman ever knew growing up was of a light-skinned, long-haired, blue-eyed man in a white robe with a beard.

Ironically, by 1970, the quickest way to arouse suspicion among many churchgoers in rural America was to look like Jesus.

It’s been 50 years since Hanaman took charge as a newly ordained minister of two small United Methodist churches in southern Wisconsin farm country.

The beard on their new shepherd immediately rendered the flock uneasy.

At that time in American society, a beard signified allegiance to the countercultural cause.

And Hanaman proved to be every bit as young and idealistic as the congregations feared.

His sermons touched regularly on the cascading tragedy of Vietnam.

After six months, the congregations asked him to leave.

He held on for another six months.

“It was a painful year,” Hanaman, now 75, recalled on a recent morning while sitting in the yard of his property near Rippey. “But I began speaking my mind.”

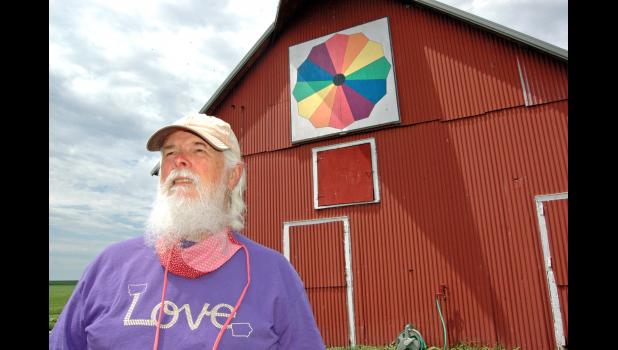

Fifty years later, Hanaman — more bearded than ever — is still finding ways to confound small-town America.

Called to action by the May 25 murder in Minneapolis of George Floyd, a Black man, by a white police officer, Hanaman has led a silent march each week at noon on the sidewalk around the Greene County courthouse as a show of solidarity with protests worldwide seeking an end to systemic racism.

Some weeks, he’s joined by just a few like-minded souls. One week, their ranks swelled to more than three dozen, each holding signs declaring, “Enough is enough,” “Silence is violence” and “Racial prejudice is learned,” among other sayings.

“There are people in Greene County,” Hanaman said, “who feel these issues are of utter importance.”

But the sight of a Black Lives Matter protest in Greene County — a place that’s 97 percent white, according to census data — has clearly pushed some people out of their comfort zones.

Criticism on Facebook has ranged from “ALL LIVES MATTER” to calling the protestors a “special kind of stupid” for “protesting a false narrative.”

“What is wrong with these people?” one person wrote on Facebook. “Don’t they have jobs?”

“It’s touching a nerve,” Hanaman said. “Our presence is raising a question those persons don’t want to deal with.”

There have been hecklers as well.

Hanaman — who retired to rural Greene County in 2007 with his wife, a Greene County native, after nearly 40 years as a United Methodist minister — was admittedly caught off guard the day someone driving by yelled, “You’re all white fools!”

If anything has changed about Dale Hanaman in the 50 years since his first job out of seminary, it’s his ability to absorb criticism.

Being asked to leave his first church had been, at best, a humbling experience. “The world had crashed,” Hanaman recalled.

These days, he takes being called a “white fool” in stride. He also doesn’t necessarily disagree with the guy who shouted it.

“You can be a stupid white fool,” Hanaman reasoned, “or you can be a good white fool.”

Hanaman is striving for the latter.

“I am racist,” he said matter-of-factly, a book about civil rights icon Rosa Parks momentarily set aside on a nearby table. “I think we live in a racist society.

“But what we do with it once we become aware of it is different.”

At age 75 with five grandkids — two of whom are multiracial — Hanaman has decided that, like the sign says, “Enough is enough.”

“Tolerant was my father,” he explained. “To be anti-racist is what we need to be about.”

His hometown of Beloit, a small hub of manufacturing located in southern Wisconsin, had a nonwhite population in 1960 of 6.6 percent — second-highest in the state behind Milwaukee at the start of the ’60s.

Even still, unspoken segregation persisted. Blacks had their side of town; whites had theirs.

Hanaman, who graduated from high school in 1963, explained that his father, a security guard at Fairbanks-Morse & Co. — a preeminent manufacturer of engines and hulking locomotives — believed that good Blacks were an exception, not the rule.

Racial slurs weren’t uncommon.

Hanaman recalls being involved in DeMolay, a Masonic youth organization for boys, until the day they and their female counterparts, the Rainbow Girls, were dressed down by the Masons for inviting a light-skinned Black boy to a joint function.

“That,” he remembers being scolded, “will never happen again.”

“That” was never actually specified.

“But we knew,” Hanaman said. “I really lost interest in the Masonic process at that point.”

The thinking, Hanaman explained, was that Black Freemasons had their own lodge in town — there they should stay.

Hanaman soon found himself on the receiving end of a higher calling.

Almost like it happened yesterday, he recalls the day in social studies class his senior year when they went around the room, each of them saying what they wanted to do after graduation.

“I said I was going to be a minister,” Hanaman said, “and there was great laughter.”

Even the teacher laughed.

“Now tell us what you really want to do,” she asked.

“So I repeated my answer,” he said.

On the recommendation of his minister, Hanaman’s journey would begin in Indianola, Iowa, at Methodist-backed Simpson College. There, he met his future wife, a Greene County gal named Nancy Bardole.

From Simpson in 1967, it was off to the Boston University School of Theology, the oldest United Methodist seminary in North America, and the place where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. had become the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. with the award of a doctorate in 1955.

With the war in Vietnam raging, an influential moment during his time there occurred when two AWOL soldiers were given sanctuary in the school’s chapel before their retrieval by the FBI.

Needless to say, however, Hanaman was hurtling along on his own collision course — and the ensuing clash of cultures would see a young minister moved twice in as many years.

Admittedly, he always loved the peace and quiet of rural Greene County whenever he visited.

“I thought this would be a great place to live,” Hanaman said.

But something about the events Hanaman saw unfolding on his TV in late May, following the death of George Floyd, ignited inside him like napalm.

In cities big and small, a new protest movement was being galvanized by the notion, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere” — words originally written by Dr. King in a 1963 letter to white clergymen who criticized his protest tactics.

Seeing as how “everywhere” does technically include Greene County, Iowa, Hanaman dashed off an email on a Friday night to 25 people, asking them to meet the very next day at the courthouse for a local show of support for what was happening across the nation.

“Lo and behold,” he said, “10 people showed up.”

The marches will continue indefinitely on Tuesdays at noon, Hanaman said. Anyone is welcome. He even has ready-made signs.

“If what we’re doing makes no difference at all,” he said, “we’re in big trouble.”

Hanaman maintains that he’s not doing anything extraordinary.

“I just happen to be the one that sends out the reminder,” he said.

The Rev. Julie Poulsen, pastor of the First United Methodist Church in Jefferson and a regular march participant, said she sees in Hanaman a “deeply compassionate Christian and pastor who is a good organizer and a strong leader for social justice.”

“I’ve been heartened by the participation,” Poulsen added, “and I’m not surprised people disagree. I’m saddened people misunderstand why we’re doing it.”

The protestors aren’t against law enforcement, Poulsen insisted.

“Some people think in a very either/or concept,” she said. “We’re so grateful for the good police officers.”

They are, however, against what Poulsen called a minority of police who’ve become akin to “judge, jury and executioner.”

Early on, Hanaman said, a Jefferson officer drove up, rolled down his window and said, “If you have any difficulty, give us a call.”

“That was very encouraging,” he said.

“We know police lives matter,” he explained. “We know soldiers’ lives matter. We know nurses’ lives matter.

“We don’t always acknowledge that people of color matter.”

That’s obviously harder than it sounds.

Some of the most vocal opposition to the weekly demonstrations has come from those who quite loudly identify as Christians. Pushback from certain congregations in the community even forced Poulsen to issue a disclaimer that the marches aren’t connected to the Greene County Clergy Association.

At the United Methodist Church in Jefferson, on the other hand, the recent action has led to the formation of a new book study that started meeting via Zoom to discuss “So You Want to Talk About Race,” a 2018 best-seller by Ijeoma Oluo.

“People would like their religion to be different than the real world,” Hanaman said. “We need to constantly be keeping in mind that the world is changing, and that our faith needs to change along with it.”

Fifty years after Hanaman joined the ministry at a time of social upheaval, there’s still no easy way to shepherd the flock.

“Why not stand up for people who have no voice? Why not stand with people who are oppressed?” he asked. “It’s not new to say, ‘Remember those who are lost or broken.’”

- Log in to post comments