A bumper crop of girls

By ANDREW MCGINN

Nearly 20 girls assembled on a recent day in the vo-ag room at Greene County High School, each sporting a jacket of deep blue corduroy that has identified scores of students since 1933 as proud members of FFA.

The occasion was a photo op with their chapter’s first female member, Joyce Allender, 50 years after she broke through a glass ceiling at the high school that kept vocational agriculture classes off limits to girls.

“It’s great. I’m always amazed,” Allender, 66, remarked as she surveyed a group of girls that seems to get bigger with each passing year.

For people of a certain age, it’s fun to point out the trivial things that today’s teenagers don’t know — like not knowing how to use a rotary-dial phone or not knowing a time when there were only three channels on TV to watch — as if to imply they missed out on some golden age.

But they also don’t know the pervasive sexism that prohibited girls from showing livestock in 4-H and barred them from FFA.

For Joyce Allender, who fought to do both, what’s really rewarding is seeing her own daughter, Conner, a sophomore at Greene County High School, clad on this day in a blue jacket — and knowing that Conner is none the wiser.

“She acts the way I always wanted to act,” Allender observed. “She wears boots and jeans every day.”

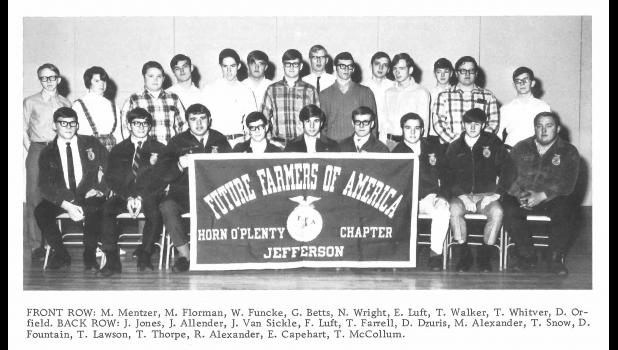

Fifty years after FFA — still known at the time as Future Farmers of America — opened membership nationally to girls in 1969, the chapter at Greene County High School looks nothing like the one pictured in that year’s yearbook.

“It looks odd that I’m the only one in there,” Allender said, inspecting the photo of 23 students, all of them male except her.

And, wait, is that a plaid jumper she’s wearing?

A 1970 graduate of what was then Jefferson Community High School, Allender never did get a blue corduroy jacket, for reasons she now can’t remember.

In all likelihood, it was because jackets and dress guidelines for girls had yet to be approved, and wouldn’t be until 1971.

“It didn’t bother me to be the first,” said Allender, who joined FFA her junior year. “I wanted it so bad.”

At today’s Greene County High School, boys still outnumber girls in FFA, but only slightly, said Katie Akers, the school’s agriculture education teacher and FFA chapter adviser.

Nationally, it’s about the same, with males making up 54 percent of FFA membership and females making up 46 percent.

However, seven of the local chapter’s eight officers are girls, and Greene County took an all-female contingent to the National FFA Convention last fall in Indianapolis for perhaps the first time.

For a second straight year, the chapter has a female president.

“I don’t think I’d take it lightly if someone told me I couldn’t do something,” said chapter president Kara Reed, a senior who’s been showing hogs since fourth grade.

Reed’s predecessor, Gwen Black, now a freshman agronomy major at Iowa State University, went on to become a state FFA officer and is finishing her term as Southwest District vice president.

Black recently returned from South Africa, where she attended an international leadership seminar for FFA state officers.

Admittedly, Akers initially worried that a news story highlighting the strong female presence in the high school FFA chapter — in light of it once being an all-boys’ club — might make it look as if she’s dissuading boys from joining.

But then she started hearing from other faculty advisers in the area, each of whom reported that girls are stepping up in ways that Joyce Allender could only dream about in 1969.

“It’s the girls who are willing to step up and take a leadership role,” Akers said.

“Women are uprising,” Reed joked.

On the contrary, boys seem to be increasingly at ease with the notion of girls leading.

“They’re just kind of chill,” Reed said.

It was a different story when Allender was coming of age: Boys and girls had distinct roles, and society did its best to ensure that neither drifted into the other gender’s lane.

Growing up on a farm in Greenbrier Twp., Allender remembers being told she couldn’t show her family’s Holsteins in 4-H. Only boys could show livestock.

Instead, she reluctantly did what was expected: sewing and baking.

“I didn’t like the girls’ part,” Allender said. “I had enough of cooking. From the time you could pick up a pan, you were expected to do that.”

In reality, she loved working alongside her dad on the farm, “which was so much better than staying in and dusting,” she said.

“It felt more comfortable,” Allender said, “like I belonged there.”

She and Conner are today starting their own herd of Highland cattle, a breed known for its long horns and shaggy hair. They have three to start.

They also have chickens of all different varieties — the benefit of living in the country.

Before moving, the Allenders unsuccessfully lobbied the Jefferson city council to allow people to keep chickens within the city limits.

It wasn’t Joyce Allender’s first fight.

“I fought to get into vo-ag,” she said.

In those days, “You had to be manly,” Allender said of the high school’s agriculture classes.

She nevertheless persisted, finding an unlikely ally in Dirk Miller, the vo-ag teacher who had started his career at Jefferson High School the summer before Pearl Harbor in 1941.

“He was interested in furthering ag any way he could,” Allender said.

By the winter of 1969, Allender was enrolled in a vo-ag class, still the main requirement for membership in FFA.

Nationally, FFA had already voted twice against girls joining, first in 1967 and again in ’68.

Before the ban was finally lifted in 1969 — a restriction that had been in place ever since the organization’s founding in 1928 — girls could only be in FFA as a chapter’s “sweetheart,” a kind of social ambassador that entitled them to wear a white corduroy jacket.

Why they didn’t just wear aprons is anybody’s guess.

But by 1969, there was no denying it: The times they were a-changing.

Allender was finally allowed to show cattle her senior year.

By the early ’70s, Miller was even offering “Agriculture Management for Women” as a continuing education class for local adults.

“There’s women in every facet of farming now,” Allender said.

In fact, women farm more than 9.1 million acres in Iowa, and make up 25 percent of the state’s farmers, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Nationally, the numbers are even higher: 31 percent of American farmers are women.

This past fall, Iowa State debuted “Women in Agriculture and the Food System,” the first class of its kind to examine the history and changing role of women in U.S. agriculture. It will be offered again this fall.

And locally at Greene County High School, Katie Akers now occupies the position once held for 33 years by Dirk Miller.

“It’s no longer taboo for us to be in these roles,” explained Akers, a 2011 graduate of Panorama High School in her fourth year teaching at Greene County.

Akers, whose Panorama FFA jacket hangs in her classroom, plans to one day take over her dad’s cattle operation southwest of Panora.

The fact that she’s an only child might have spelled doom a generation ago for a family farm.

No longer.

“The family farm doesn’t have to just stop because there’s no son,” she said.

There’s no denying that farming remains a dangerous vocation, Akers said.

“A shout-out to our dads, who included us,” she said. “And a shout-out to our moms for letting us.”

Because the ag industry is so vast, participation in FFA is today viewed more as a way to grow leaders than farmers. Kara Reed, the current Greene County president, wants to be an optometrist.

For that reason, Future Farmers of America has been known as simply FFA since 1988.

Agriculture, though, remains the heart and soul of FFA. Plans are underway for a 40-acre FFA farm at the site of the new Greene County High School, set to open in 2020 along U.S. Highway 30 in Jefferson.

But the real story of FFA in the 21st century might be its sheer size.

Membership nationally has exploded from 260,300 members in 1948 to 669,989 members today. Since 2008, FFA has averaged 15,000 new members annually.

The chapter at Greene County High School now boasts 63 members, and momentum keeps building.

“After seeing all the kids in their jackets, I thought that was cool,” said junior Tieryn Tucker, who joined her sophomore year and is now the vice president.

They’re all fairly certain that FFA is now the largest student organization at the high school.

“We outnumber the football team,” Akers said. “I remember being proud of that one.”

- Log in to post comments